🌀🗞 The FLUX Review, Ep. 44

March 24th, 2022

Episode 44 — March 24th, 2022 — Available at read.fluxcollective.org/p/44

Contributors to this issue: Neel Mehta, Justin Quimby, Ade Oshineye, Alex Komoroske, Boris Smus, Ben Mathes, Erika Rice Scherpelz, Spencer Pitman, Julka Almquist

Additional insights from: Gordon Brander, a.r. Routh, Stefano Mazzocchi, Dimitri Glazkov, Robinson Eaton

We’re a ragtag band of systems thinkers who have been dedicating our early mornings to finding new lenses to help you make sense of the complex world we live in. This newsletter is a collection of patterns we’ve noticed in recent weeks.

“Every person alone is sincere. At the entrance of a second person, hypocrisy begins.”

— Ralph Waldo Emerson

🌃⛔️🌳 Christopher Alexander: an appreciation

Christopher Alexander has died.

Alexander was one of the most influential architects of the last century, but most of his impact was outside the construction industries despite the hundreds of buildings he designed. Instead, his fingerprints are all over codebases that touch your life every day.

Alexander’s book A Pattern Language led to the Design Patterns movement in software development. Later, he gently rebuked the same movement for failing to understand the need for patterns to be humane and habitable. In his own words:

“Does all this thought, philosophy, help people to write better programs? For the instigators of this approach to programming too, as in architecture, I suppose a critical question is simply this: Do the people who write these programs, using alexandrian patterns, or any other methods, do they do better work? Are the programs better? Do they get better results, more efficiently, more speedily, more profoundly? Do people actually feel more alive when using them? Is what is accomplished by these programs, and by the people who run these programs and by the people who are affected by them, better, more elevated, more insightful, better by ordinary spiritual standards?”

After that, Alexander’s group published The Timeless Way of Building, which described the theoretical and philosophical underpinnings of pattern languages while also connecting ideas such as the quality without a name and generativity to Gall’s Law. Then, his 4-volume series The Nature of Order took those same ideas from the geometric to the cosmological.

Alexander’s overlap between architecture and software is less surprising when you learn that he studied math before becoming an architect. His seminal essay A City is Not a Tree is not about arborescent plants but rather data structures: he was saying that a city is not a hierarchical tree data structure but a lattice, where some parts of cities don’t belong to just one thing in the hierarchy. For example, at work, your org structure is probably a strict tree: you only report to one manager, and so do they, and so on. But your actual work cuts across the org structure, touching many different areas. The same goes for most human organizations like clubs, cities, states, companies, teams, and so on. You feel this same tree-vs.-lattice tension whenever you try to put files into folders, but each file sort of belongs to more than just one folder.

Over the decades, Alexander tried to teach us how to build structures (from objects to artworks to homes to communities to entire regions) that have the quality without a name, wholeness, habitability, “life.” These qualities all signal that these structures are better for humanity. Unfortunately, Alexander’s death means we will never see what he had in mind for his final book, Sustainability and Morphogenesis.

Alexander gave us the conceptual tools to make systems generate other systems and the ability to enact structure-preserving transformations (more commonly known as refactoring) so that we can maintain and improve these living systems.

His legacy is a set of tools: a set of tools that help us be good stewards of what we inherit. A set of tools that help us be good ancestors. A set of tools that might just provide our successors with systems that are worth keeping alive.

🛣️🚩 Signposts

Clues that point to where our changing world might lead us.

🚏📥 Downloads of Russian Wikipedia have increased 40x amid fears it’ll be banned

In early March, the Russian government threatened to ban Wikipedia from the country. In response, Russian residents have been flocking to download copies of the Russian-language Wikipedia, whose 1.8 million articles weigh in at 29 GB. The organization that bundles Wikipedia for download says downloads of the Russian-language encyclopedia have increased 40-fold since January, and Russian users currently make up the vast majority of the site’s visitors.

🚏🕹 Fortnite has raised at least $36 million for Ukraine relief

Epic Games, the makers of Fortnite, announced that, for two weeks, all its proceeds would be donated toward “humanitarian relief for Ukraine.” Just a day into the pledge, Epic announced it had raised over $36 million, with the funds being sent to international organizations like the World Food Programme (WFP) and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

🚏🏎 A gamer made a script that automates “grinding,” avoiding pricey microtransactions

A recent change to a car-racing video game sharply reduced the number of in-game credits players earn by winning races, nudging them to spend real money if they want to buy fancy virtual cars. So one player found a way to use PC scripting to automatically send a sequence of choreographed button presses to the game, letting players sit back and repeatedly win races. Players using this script can earn millions of in-game credits a day without lifting a finger, thus avoiding “hundreds of dollars in microtransaction costs.”

🚏📱 US states are launching probes into TikTok’s effects on kids’ health

In recent years, American legislators have been pressuring social media platforms to increase privacy protections for children, and TikTok in particular has drawn allegations of enabling abuse, bullying, and self-harm. This month, attorneys general from at least eight states launched investigations into TikTok’s possible harmful effects on youths’ mental health.

🚏🎈 An NFT project inflated its floor price by destroying tokens listed for sale below it

For NFT projects, a key metric is the “floor price,” or the minimum selling price of any token in the collection. In a seeming attempt to game this metric (and a great example of Goodhart’s Law in action), one NFT project set up a novel mechanic. For each of the first five days of the project’s existence, the minimum listing price would increase — and the smart contract powering the tokens would automatically destroy any token listed for sale below that threshold. The “burn schedule” would eventually cap out at 0.64 ETH, or about $2000.

🚏☣️ An AI designed 40,000 possibly-toxic chemicals when its methodology was tweaked

A team of scientists were building an ML model that would predict how toxic a given chemical would be; the outputs of this model could be used to screen potential pharmaceuticals. As an experiment, the team switched the ML model to go from optimizing for the least toxic chemicals to optimizing for the most toxic chemicals. In less than six hours, the AI spat out formulas for 40,000 “potentially lethal” chemicals, including some deadly nerve gasses that have been used in warfare — and some chemicals predicted to be even more deadly.

📖⏳ Worth your time

Some especially insightful pieces we’ve read, watched, and listened to recently.

Most Dictators Self-Destruct. Why? (Bloomberg) — A political scientist argues that most instances of democratization aren’t intentional but rather the results of blunders by dictators. These autocrats’ mistakes come in five main flavors: hubris (underestimating the opposition’s strength), taking needless risk (like starting unwinnable wars), slippery slopes (where small reforms eventually lead to regime collapse), trusting disloyal people, and using needless violence. These blunders often build on each other. Hubris, for example, could lead an autocrat to think that an unwinnable war is winnable.

The Sanction-Fueled Destruction of the Russian Aviation Industry (Wendover Productions) — Shows how sanctions have effectively pushed Russian aviation back to the Cold War era, isolating it from the interconnected global aviation system. Then examines how the closure of Russian airspace to the West might increase the strategic value of certain airports and enable airline business models that haven’t been feasible since the 1980s.

Protopia (Kevin Kelly) — Argues that pure utopias and pure dystopias can never exist for long before they revert into a different form of governance. Instead of only envisioning utopias and dystopias (or, worse, completely avoiding any thought of the future), futurists should imagine “protopias”: plausible worlds that are a little better than our current one.

Why Cisco’s ‘Spin-Ins’ Never Caught On (Financial Times) — Examines how, in the 1990s, Cisco pioneered a model where employees would leave to found a startup; if the company hit certain short-term goals, Cisco would have to acquire it. The model looked good on paper, but it bred resentment among less-entrepreneurial employees and still held downsides for the “spin-in” entrepreneurs, who would end up with nothing if the acquisition didn’t happen.

The Yosemite Fires: Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Wisdom (Atmos) — Details how early Euro-American naturalists embraced the myth of a “pristine wilderness” in places like Yosemite, overlooking the fact that Native Americans had purposely intervened in the landscape with strategic burns to maintain the ecosystem’s health and biodiversity.

Time Has No Meaning at the North Pole (Scientific American) — Explores life aboard a research ship parked in the Arctic Ocean at the North Pole, where time zones become arbitrary and, during the endless polar nights, the very concept of a “day” becomes fuzzy. Reflects on how this is a reminder that time is just a useful human construct.

Amazon Shareholder’s Letter (2005) (Amazon) — Jeff Bezos explores the limits of math and data, conceding that many important decisions cannot be made in a math-based way. He laments that “math-based decisions command wide agreement, whereas judgment-based decisions are rightly debated and often controversial, at least until put into practice and demonstrated.” Alas, complexity!

There’s Something Off About ApeCoin (Platformer) — Casey Newton argues that there’s a subtle reason for the surging popularity of venture-backed DAOs: issuing crypto-coins that can be sold well before a company goes public lets VCs recoup their investments early. If you squint, it’s like “a SPAC without the legal protections a SPAC offers investors.”

🌀🖋 More from FLUXers

Highlighting independent publications from FLUX contributors.

Alex Komoroske’s Medium posts often start with a metaphor and then spend the remainder of the space unpacking that metaphor. His most recent post, The Wanderer and the Seeds, skips that second part, resulting in a modern-day parable about wandering, seeds, trust, and shared rituals that leaves it to the reader to extract their own meaning.

📚🌲 Book for your shelf

An evergreen book that will help you dip your toes into systems thinking.

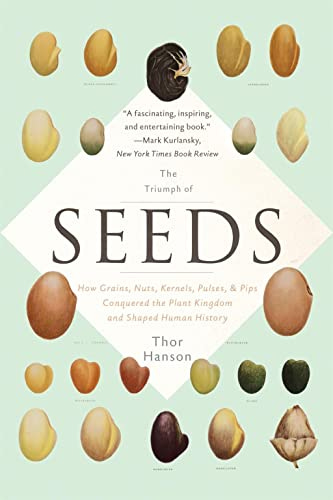

This week, we recommend The Triumph of Seeds by Thor Hanson (2015, 320 pages).

We eat them, we plant them, we save them, but what are seeds? In this book, Thor Hanson explores the complex and astonishing world of seeds. It’s not a biological focus on how a seed becomes a plant, but rather a richer exploration of their history, adaptations, and essential role in our world.

Plants have a big evolutionary disadvantage: they stay in one place. The fundamental purpose of seeds is to ensure their plant species survives, and the primary reason they’re able to do this is because they can move. A fascinating evolutionary adaptation is that seeds come pre-packed with food and are ready to grow; Hanson describes them as a “baby plant, in a box, with its lunch.” Having energy concentrated into a little package also allows them to stay dormant for a very long time and opens up more possibilities for movement. They collaborate with the wind, waves, birds, our shoes and clothes, or any other opportunity that helps them find the right conditions to grow.

This book is a prismatic exploration with seeds at the center. It invites you to be curious about systems and collaboration, to ask new questions, and to see the world around you in new ways.

🕵️♀️📆 Lens of the week

Introducing new ways to see the world and new tools to add to your mental arsenal.

This week’s lens: lens types.

Let’s go a bit meta this week. In a complex world, we have to apply lenses to make sense of things. This newsletter’s Lens of the Week section is a direct encouragement to take different lenses for a spin, to hold them lightly. As we play with the lenses, we might notice that some are more difficult to hold than others. What gives? Perhaps one way to parse this tension is to sort lenses by their depth.

Truth lenses

Truth lenses allow us to play with facts. We know gravity exists, but what would happen if there wasn’t gravity? Such thought experiments emerge early in our lives, opening space for wild imagination, helping us acquire new facts, and occasionally showing us new wisdom hidden between known facts. The truth lens is easy to hold because it plays within the limits of an existing definition.

Semantic lenses

To play with the idea of non-existent gravity, one needs to have an understanding of what gravity is. But what if gravity was something completely different? Semantic lenses allow us to change how something is seen, a technique commonly called reframing (or just framing). The shift from gravity as an interaction between masses to gravity as a warping of spacetime is just such a shift. Semantic lenses see deeper than truth lenses. But this same depth makes them harder to hold. The set of possibilities explodes, now representing multitudes of possible truths. Yet, for all their difficulty, semantic lenses are still constrained by the way we make meaning of the world around us.

Ontological lenses

Ontological lenses see deeper still. When we think about gravity, what are our underlying beliefs about entities and their interactions? Does the very idea of an “interaction” change if we stop drawing boundaries between entities? If semantic lenses are like shifting our vantage point, ontological lenses are like suddenly seeing in infrared. These lenses can be the hardest to hold. We sense that they can cause us to question our core beliefs. Opening ourselves to this discomfort can be hard, but the results are often worth it.

(If you’re keen on digging deeper into this topic, check out the paper that inspired this piece: Ontological Uncertainty and Innovation by David A. Lane and Robert M. Maxfield.)

🔮📬 Postcard from the future

A ‘what if’ piece of speculative fiction about a possible future that could result from the systemic forces changing our world.

Content Tag: This week’s postcard indirectly references the ongoing violence in Ukraine.

// What might be the follow-on implications of the Russian military’s logistical failures during the invasion of Ukraine?

// March 2035. Introductory lecture to “Forensic Accounting 101.”

Many of you are here because of a surge of interest in accounting in the mid-2020s, when you were in middle school. I’m here to tell you that the realities of investigating where the money goes is not like it’s portrayed in the movies or what you saw on YouTube. Sure, while there was a flurry of work on exposing crypto scams and influencers in the early 2020s before the burst and rebuild, the real precipitating event for interest in forensic accounting was the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Early on in the war, media coverage focused on the logistical failures that severely hampered the Russian military’s invasion of Ukraine. Soldiers sent to war with 20-year-old rations. Tanks out of fuel being towed by Ukrainian farm equipment. Forty-kilometer-long stalled columns of troops and vehicles.

As Russia’s military ground to a halt through the end of 2022, a wave of near-panic washed through the halls of the Pentagon. That panic could be described as, “we can’t look like the Russians.” The logistical failures pointed to a degree of Russian corruption many thought not possible in a modern military. Rocks put into fuel tanks to cover for the stolen fuel. Inventories triple- or quadruple-counted to cover for vehicles sold to warlords.

Calls to ensure that the US would not get caught with its pants around its ankles led to a surge of interest in tracking the over $770 billion annual US military budget. Most disconcertingly, the US military had failed every single annual audit since 2017. This concern over “are we ready?” became a talking point taken up by both political parties and a staple of discussion on the 2022 campaign trail.

This was not the first time the Pentagon had had to scramble, either. Almost a hundred years ago, the US Senate investigated military waste and profiteering for immense sums. That committee spent $360,000 to save an estimated $10–15 billion, a 41,000x return on investment — to say nothing of the lives saved. To give you a sense of scale, the entire Manhattan Project at the time cost $2 billion. The lead senator behind this investigation went on to become US President.

Cable news pundits and TikTok insta-experts tore into military spending reports, hunting for any sign of malfeasance. 2022 and 2023 saw multiple massive scandals as the sloppiness of defense spending was revealed. It was easy pickings for politicians, journalists, and the interested public. A Navy warehouse not on the property books with $125 million of supplies. Purchases of $10,000 leather chairs. Backup parts purchased for weapon systems that had not yet been designed.

As General Omar Bradley famously said: “Amateurs talk strategy. Professionals talk logistics.” Which is why you are here. You saw the Insta posts and Tweets of “a big fraud revealed.” You saw the campaign ads calling for “responsibly spending our tax dollars.” The public shaming of officials and subcontractors made for great media clips and large follower counts. Well, I’m here to tell you that it doesn’t always go that way. But if you enjoy the puzzles, and want to make the world a better place, welcome. Now let's get to work.