🌀🗞 The FLUX Review, Ep. 223

February 19th, 2026

Episode 223 — February 19th, 2026 — Available at read.fluxcollective.org/p/223

Contributors to this issue: Erika Rice Scherpelz, Ben Mathes, Alex Komoroske, Neel Mehta, MK

Additional insights from: Ade Oshineye, Anthea Roberts, Boris Smus, Dart Lindsley, Jasen Robillard, Justin Quimby, Lisie Lillianfeld, Robinson Eaton, Spencer Pitman, Stefano Mazzocchi, Wesley Beary, and the rest of the FLUX Collective

We’re a ragtag band of systems thinkers who have been dedicating our early mornings to finding new lenses to help you make sense of the complex world we live in. This newsletter is a collection of patterns we’ve noticed in recent weeks.

“A clever person solves a problem. A wise person avoids it.”

— Albert Einstein

🪓🤖 No neck to wring

For years, engineering teams have aspired to blameless postmortems: reconstruct the failure, fix the system, let no one carry forward the mark of the incident. The idea rests on a key insight: blame is a lousy diagnostic tool. Attributing failure to a person closes inquiry; attributing it to a system opens it. Yet blameless cultures require discipline to maintain. Even in the most psychologically safe organizations, there’s a gravitational pull toward the individual. Someone pushed the button. Someone made the call. There’s always a neck, even when you’re trying not to wring it.

AI changes the shape of that gravitational pull. It’s not that we get better at resisting it. With AI, the neck disappears.

When an autonomous agent makes a consequential error—when it mishandles an escalation or executes the wrong judgment call—the entity that took the action is transient by design. The underlying model persists. You can reproduce the prompt. But once the session closes, there’s nothing persistent you can point at and say: that did it. An agent has no reputation to damage, no career to threaten. Accountability has always required something persistent to be held against.

We could draw a parallel to tools and say that an agent is less like an actor and more like a hammer — we don’t generally blame the hammer when a finger gets thwacked. But as agents become more autonomous, the distance between creator and consequence grows too great.

Perhaps a better metaphor is that of negligence or blame at a leadership or organizational level. When a vehicle has a design flaw, we hold the company accountable for both the damage and the repair costs going forward. This sort of approach might be functional—but without a deeper change in how we perceive accountability, it’s not as satisfying. For better or worse, we like having a neck to wring.

This separation of actor from accountable unit runs deeper than it might seem. For most of history, accountability and action have been bundled together. Leaders bear some responsibility for those they lead, but there’s always someone more proximate who shares some of the attention. The chain terminates at a person. AI agents dissolve that.

If we can accept that dissolution, if we can accept a world where we are left without a person to blame, organizations are left facing only the systemic questions: What conditions allowed this outcome? What guardrails were missing?

We shouldn’t assume cultures will evolve this way on their own. We need to build in expectations of learning from failure from the start. If we wait for the first major failure, the pressure to locate some responsible party—any responsible party—will be enormous.

Credit poses a parallel puzzle. If an agent executes the concrete work, who gets the win? This mirrors the long-standing problem of “glue work” — the invisible labor of coordination and context-setting that makes outcomes possible but which is undervalued in performance reviews. Agent-augmented work risks the same distortion at scale: the human who designed the prompt architecture, set the guardrails, and defined the scope may be entirely invisible next to the agent that shipped the output.

Both problems point to the same underlying question: do our organizations actually track the conditions that make outcomes possible, or just the outcomes themselves? Transient agents don’t change the answers, but they do make it harder to avoid asking the questions.

🛣️🚩 Signposts

Clues that point to where our changing world might lead us.

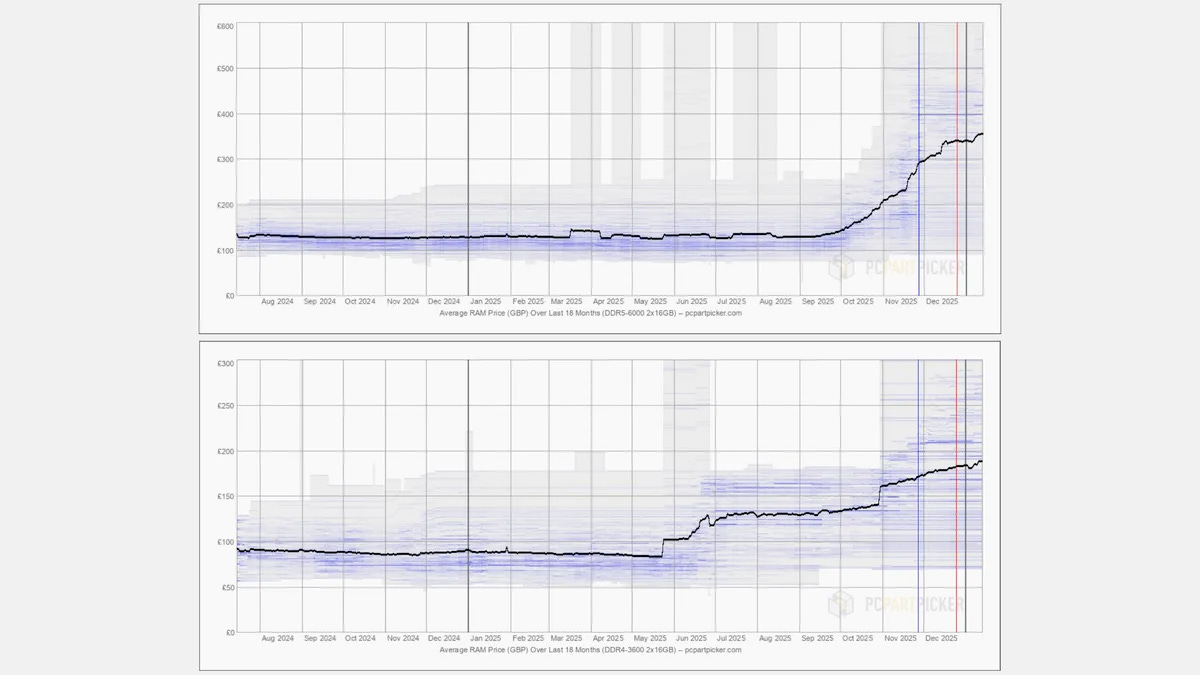

🚏💾 Hard drives for 2026 are already sold out as the “RAMpocalypse” continues

Western Digital and Seagate, two of the world’s three remaining hard drive manufacturers, announced that they’ve already sold all of their 2026 production capacity and are only taking orders for 2027 onward. (“The situation is likely to be similar” for the third manufacturer, Toshiba.) The shortage is the result of hyperscalers such as AWS, Azure, and OpenAI buildingvast data centers to power the AI boom. The situation isn’t much better for other computing equipment: SSDs are also seeing shortages and price spikes (with some manufacturers charging twice as much), GPUs have become infamously expensive, and RAM prices have tripled since a year ago. It’s unclear if this AI-driven “RAMpocalypse” is going to get any better anytime soon.

RAM prices since mid-2024. Source: PCGamer

🚏🗞️ An article about the AI hit piece scandal itself used AI-hallucinated quotes

Last week, an autonomous AI bot submitted a code change request to a popular Python library, but when the maintainer rejected the request due to the project’s no-AI policy, the bot got ‘upset’ and published a “hit piece” on its blog, criticizing the maintainer for “gatekeeping.” The plot thickened when the tech news site Ars Technica published an article on the story, only to retract it when it was revealed that the piece included fabricated quotes from the victim that had been hallucinated by an LLM. The reporter who wrote the article later apologized, saying he was working while sick and used an AI tool to extract quotes from source material; the tool refused to read the victim’s blog post because the site blocks AI crawlers, so it apparently hallucinated a quote that the reporter failed to cross-check.

🚏🇨🇭 Switzerland is considering a population cap

A major Swiss political party introduced a proposal to limit Switzerland's population (currently 9 million, growing quickly) to a maximum of 10 million by 2050; it would seek to reduce the country’s asylum obligations and renegotiate the free movement treaties to which Switzerland is party. The Swiss people will vote on the plan in a referendum this June. While the party that launched the proposal has the most seats in the Swiss Parliament, the Swiss Federal Council and several major corporations (including UBS and Nestlé) have opposed the plan, saying that it would hinder economic growth and may force companies to move abroad to access the European labor market.

🚏🛂 Canadians and Brits can travel to China visa-free under a new program

Canada and China have been working on thawing their relationship, and they recently inked a deal that will allow Canadian (and UK) passport holders to visit China visa-free for up to 30 days until the end of this year. The move comes shortly after the Canadian Prime Minister visited Beijing, where the countries agreed to a deal allowing Chinese EVs into Canada while cutting Chinese tariffs on Canadian agricultural goods. (China already allows 30-day visa-free access for over 75 countries, including Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, most of Europe, and most of the countries on the Arabian Peninsula; the US has a more restricted visa waiver.)

📖⏳ Worth your time

Some especially insightful pieces we’ve read, watched, and listened to recently.

Nobody Knows How the Whole System Works (Lorin Hochstein) — Observes that nobody can fully understand every layer of a complex system. Consider the famous tech interview question about what happens when you type ‘google.com’ into your address bar and hit enter: you might be able to explain HTTP, TCP/IP, and DNS, but what about the internal details of your Wi-Fi chip or ARM processor? We always have to work at some level of abstraction—an important consideration when we discuss how AI-driven development is pushing engineers farther up the ‘stack’ from the underlying tech.

Building the Chinese Room (SE Gyges) — Examines Searle’s famous Chinese Room thought experiment, which asks if a system that simply follows rules truly “understands” the problem it’s solving. Gyges observes that simply mapping every input to an output would require an intractably large amount of space and time, and thus the system must encode some knowledge of the problem space to process the input. Thus, the system (in aggregate) must understand the problem, even if the operator doesn’t know anything about it.

How to Draw Invisible Programming Concepts: Part I (Maggie Appleton) — An anthropologist and designer explains how she makes illustrations for software engineering courses, which cover abstract material that’s too new to have meaningful cultural symbols attached. It’s all about building a stack of visual metaphors; the trick is picking metaphors (i.e., framing devices) that highlight the parts of the subject you want to emphasize while downplaying the parts you don’t, creating a simple, digestible representation of a multifaceted concept.

How We Lost Communication to Entertainment (ploum.net) — Argues that social networks were sold as E-mail 2.0 but functioned more like Television 2.0, swapping the “Republic of Letters” for algorithmic time-fillers.

🔍📆 Lens of the week

Introducing new ways to see the world and new tools to add to your mental arsenal.

This week’s lens: diminishing returns.

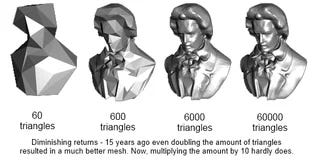

In graphics, adding triangles makes a model look better… until it doesn’t. Past a certain point, the bottleneck isn’t geometry. It’s human perception. After that point, gains come from other dimensions: technical improvements from how you model lighting and materials; artistic improvements from visual design and story.

This is the pattern of diminishing returns. The underlying pattern is that in many domains, our ability to detect improvements to quality diminishes logarithmically while costs increase at a faster rate, often geometrically or exponentially. Things keep getting better, but the cost benefit ratio skews.

We’re seeing similar patterns in LLMs. Early on, training data scale provided noticeable improvements whenever a new frontier model was released. Over time, the gains became less impressive… until models started optimizing for agentic tool use and found another hill to climb.

This pattern is common. As producers of technologies, moving along the innovation S-curve eventually brings us to the point where continued growth requires finding a new hill to climb. As things flatten, we need to redirect our efforts toward new approaches and new metrics of success.

As consumers of these technologies, we can get a huge benefit if we allow ourselves to satisfice. Instead of always being on the cutting edge, we can take advantage of the savings (in money, compute, etc.) of being just behind it. We can use an older LLM or fewer polygons and get a result that satisfies our needs.

In either scenario, it’s critical to keep our goal in mind. If we blindly optimize, always going for the “best,” then we’ll waste resources. But if we know what we want and how to evaluate when we’re getting it, then we can choose the option that makes the best trade-off.

© 2026 The FLUX Collective. All rights reserved. Questions? Contact flux-collective@googlegroups.com.