🌀🗞 The FLUX Review, Ep. 216

November 20th, 2025

Episode 216 — November 20th, 2025 — Available at read.fluxcollective.org/p/216

Contributors to this issue: Justin Quimby, Ade Oshineye, Erika Rice Scherpelz, Neel Mehta, Boris Smus, MK

Additional insights from: Anthea Roberts, Ben Mathes, Dart Lindsley, Jasen Robillard, Lisie Lillianfeld, Robinson Eaton, Spencer Pitman, Stefano Mazzocchi, Wesley Beary, and the rest of the FLUX Collective

We’re a ragtag band of systems thinkers who have been dedicating our early mornings to finding new lenses to help you make sense of the complex world we live in. This newsletter is a collection of patterns we’ve noticed in recent weeks.

“Without writing, the literate mind would not and could not think as it does, not only when engaged in writing but normally even when it is composing its thoughts in oral form. More than any other single invention, writing has transformed human consciousness.”

— Walter Ong

📝 Editor’s note: We’ll be taking the rest of 2025 off for the American holiday season. We’ll see you again in January!

🎲♾️ You can’t play infinite games without finite wins

A jazz quartet can improvise for hours, but only because each musician lands their notes, keeps time, and responds to others. The music continues by weaving together many small successes. Without these small wins, the music collapses. The infinite play of creation depends on countless finite completions.

The appeal of an infinite game is its promise of continuity, to play not to win but to keep playing. The idea has become shorthand for sustainable strategy and long-termism. But the concept can get flattened into abstraction, a focus only on the long term with no concern for the present.

In practice, every infinite game is built from a series of finite wins. Without them, the game ends. These finite wins are moments of completion: closing a deal, shipping a product, hiring a teammate, fixing a big. They are stories within the story, self-contained arcs that give the ongoing narrative momentum.

This need for finite wins highlights what infinite games are not: they are not an excuse to avoid commitment to outcomes. Nor are they perpetual motion with no direction. But we must also avoid the opposite mistake of taking short-term wins as progress toward something that lasts.

Infinite games are recursive: they consist of wins that beget other wins. These wins must tend to the system’s metabolism. Finite wins sustain this metabolism by providing the resources that replenish its energy. Without nourishment, the infinite game collapses. But an obsession with empty calories today also destroys long-term health.

This need for ongoing wins is inescapable because the risk of ruin (that’s this week’s lens) looms over every infinite game. No amount of initial resources—capital, energy, goodwill—can substitute for the capacity to regenerate. The infinite is something you must continually earn.

🛣️🚩 Signposts

Clues that point to where our changing world might lead us.

🚏♨️ Americans are trying to heat their homes and businesses with Bitcoin mining

A new space heater called the Heatbit Trio runs a Bitcoin miner under the hood and uses the waste heat to warm a room; the Bitcoin earned offsets about 20% of the electricity cost. It’s part of the growing industry of Bitcoin-powered home heating in the US, driven by rising electricity bills (which, in turn, are partly driven by the explosion of power-hungry data centers). In some American cities, industrial users like car washes and concrete companies are using Bitcoin-powered water heaters, while one New York-based spa uses Bitcoin to heat its hot tubs.

🚏🌧️ Iran is trying cloud seeding amid a worsening drought

Iran is facing its worst drought in 60 years as rainfall has dropped 89% from historical averages; the Iranian president darkly joked that they might have to “evacuate Tehran” if the water shortages continue. So, Iranian authorities have reportedly “sprayed clouds with chemicals to induce rain” above the country’s largest lake, which has almost entirely dried out. The nearby UAE has experimented with cloud seeding—spraying salts into clouds to create nuclei for potential raindrops—in the past, with some success.

🚏🇵🇪 EV sales are booming in South America, driven by Chinese brands and ports

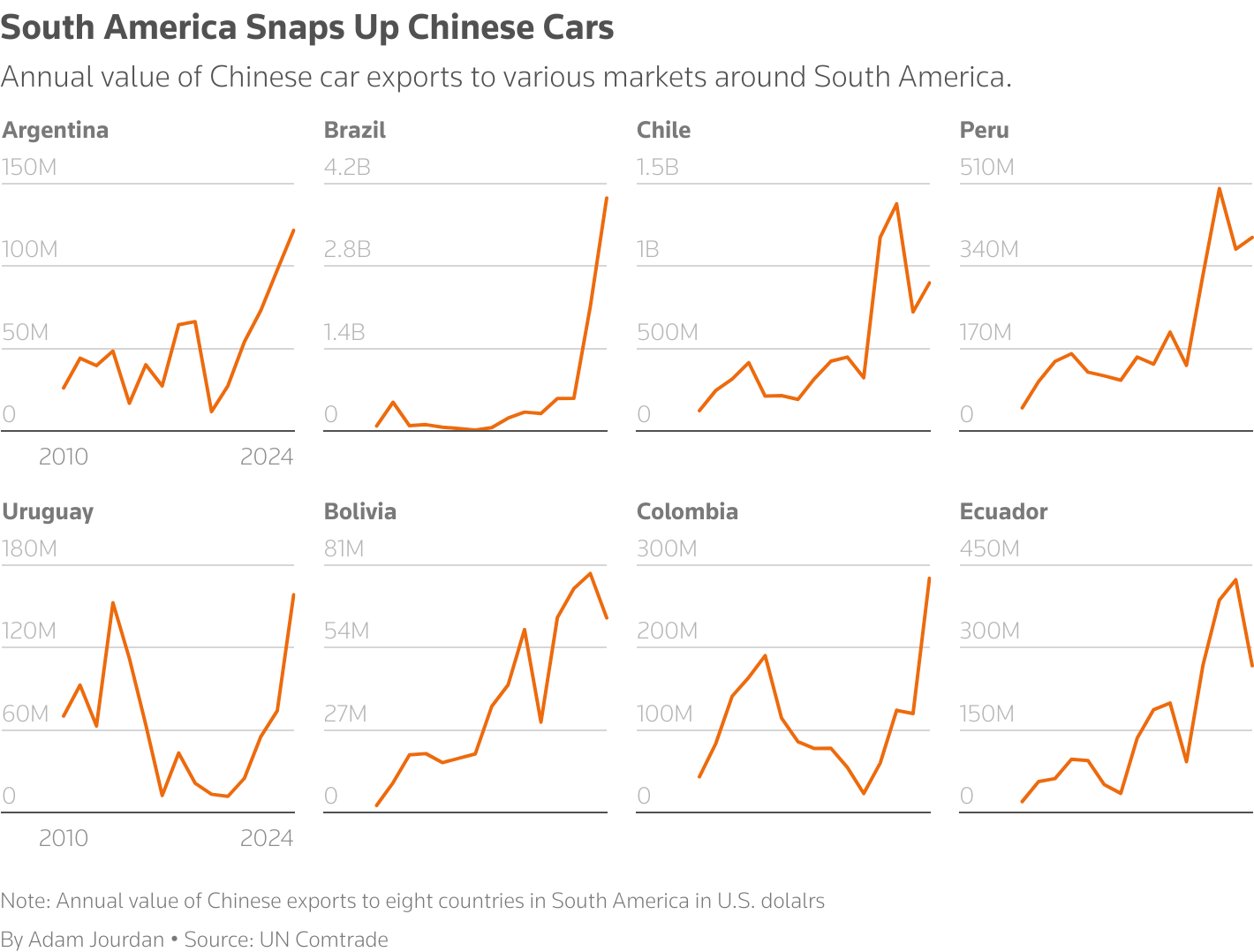

Electric cars now represent 10.6% of all new cars registered in Chile, 9.4% in Brazil, and 28% in Uruguay—all record highs. (That’s behind China at 51% and Europe at 56%, but close to surpassing the US at 10%.) In Peru, electric cars are still a small market, but sales are up 44% year over year. Chinese car brands are the dominant players in the EV space here, with BYD “lead[ing] electric car sales in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Uruguay.” (Meanwhile, Tesla only just opened its first showroom in South America.) One driver of Chinese brands’ dominance is a Chinese-built ‘megaport’ north of Lima, created as part of the Belt and Road initiative, which will bring tens of thousands of cars to the continent every year.

🚏🏘️ American homebuyers are getting older and richer than ever

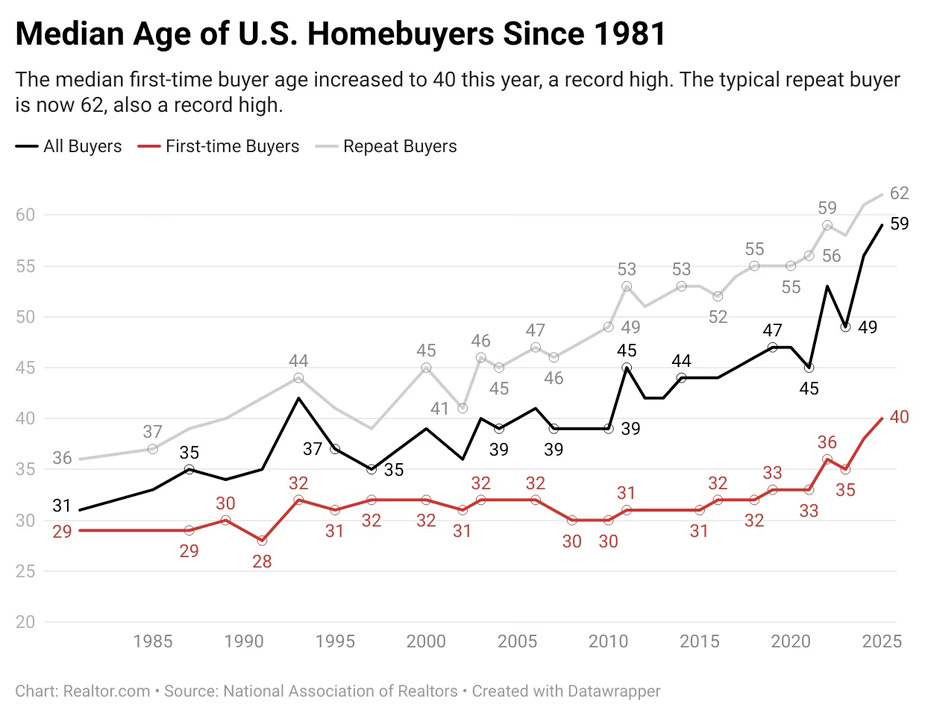

New data from the US’s National Association of Realtors shows that the median age of first-time homebuyers has reached 40, up from the early 30s just a decade ago. The median age of all homebuyers is now a staggering 59. What’s more, first-time buyers now represent just 21% of all homebuyers, a record low. The remaining first-time homebuyers seem relatively wealthy, with most using personal savings for the down payment rather than gifts or loans from friends or relatives, which were the primary methods in the past. Plus, they now put down 10% on their houses, up from 5–6% a decade ago, the highest level since 1989.

📖⏳ Worth your time

Some especially insightful pieces we’ve read, watched, and listened to recently.

Why AI Writing is Mid (Interconnects) — Argues that the blandness of LLM writing is a structural result of how models are trained, rather than a technical issue that’ll be solved if we throw more compute at it. RLHF introduces biases toward sycophantic, unchallenging, and generic prose (none of which are hallmarks of good writing); the great ‘averaging’ effect of LLMs strips away the quirkiness and uniqueness that makes written works memorable and fun; and the “forced neutrality” of language models mean that they don’t have any human opinions or perspectives, which is half the reason we read things to begin with.

Is AI Turning Music Streaming Services Into Comment Sections? (Calm & Fluffy) — Argues that our new era of AI music, where anyone can publish personalized songs and remix others’, is an odd sort of return to the traditional world of folk music, where music was participative (rather than being broadcast from certain big performers), decentralized, and specific to certain communities. Perhaps the 20th-century world of mass broadcast media, record labels, superstar performers, and homogeneous global consumption will go down in history as the exception rather than the rule.

Real Purchasing Power Over Time Is Not Economic Welfare Over Time (Steve Randy Waldman / Interfluidity) — Observes that economists track income over time because it’s easy to measure, but what they’re really trying to maximize is welfare. However, in the medium- and long-term, being able to buy more stuff doesn’t necessarily make people better off. Waldman examines a variety of factors, such as how cheaper options sometimes go extinct, forcing everyone to a more expensive option for no net welfare gain (e.g., suburbanites having to buy cars because transit-specific towns have become rare). What’s more, the composition of bundles changes over time (e.g,. housing and healthcare take up more of people’s budgets as consumer goods get cheaper), so tracking the quantity of a fixed bundle that people can buy isn’t very informative to begin with.

The Primitive Tortureboard (Marcin Wichary) — A deep dive into keyboard layouts reveals that QWERTY evolved from its inventor solving mechanical typewriter jamming issues (reducing clashes from once every 26 words to once per 1,000), while containing the suspicious coincidence that T-Y-P-E-W-R-I-T-E-R can be spelled entirely on the top row (a 1 in 5,000 chance). Alternatives like Dvorak failed not due to inferior design but because QWERTY was already good enough, and switching costs outweighed marginal benefits.

🔍📆 Lens of the week

Introducing new ways to see the world and new tools to add to your mental arsenal.

This week’s lens: Risk of ruin.

A venture capital portfolio generally has a wide distribution of outcomes. They spread their risk across many bets, and the big wins carry the rest. If success at the top is high, then the average is decent enough for them to make money.

But things look very different for the individuals within a startup. They are exploring only one path (or, at most, a relatively small number). Averages don’t matter when your success or failure is linked to any one particular outcome.

There is a critical asymmetry here. For a VC, a loss is incremental. For an individual startup, some losses end the game. This is the risk of ruin. Risk of ruin refers to events that introduce irreversible failure, a loss so severe it halts the possibility of future recovery.

Mathematically, this sort of ruin is an absorbing barrier. Once you cross such a barrier, you don’t bounce back. Ruin doesn’t always look like immediate death. For example, a species can experience functional extinction a generation before actual extinction if there are no breeding pairs left.

In this world, risk management isn’t just about spreading your bets and avoiding single points of failure. It’s about avoiding irreversible negative outcomes. Ruin is the ultimate one-way door.

The risk of ruin gets at the fundamental difference between the VC and the startup employee. The VC can think in terms of expected utility—the average of all possible outcomes. But actors on a particular path should instead look to ergodicity economics: maximizing realized wealth yields better outcomes than maximizing utility. This is true even without ruin, but ruin makes it especially stark: it doesn’t matter what happens on average if you’re dead.

The risk of ruin lens tells us that losses aren’t created equal because the average outcome doesn’t matter if you don’t live long enough to see it.

© 2025 The FLUX Collective. All rights reserved. Questions? Contact flux-collective@googlegroups.com.

This is a helpful reminder that continuity is not the same as progress. Infinite games only stay alive when enough moments actually land, close, and register as real.

Love this!