🌀🗞 The FLUX Review, Ep. 213

October 30th, 2025

Episode 213 — October 30th, 2025 — Available at read.fluxcollective.org/p/213

Contributors to this issue: Ade Oshineye, Wesley Beary, Erika Rice Scherpelz, Ben Mathes, Dart Lindsley, Stefano Mazzocchi, Justin Quimby, Neel Mehta, Boris Smus, MK

Additional insights from: Anthea Roberts, Jasen Robillard, Lisie Lillianfeld, Robinson Eaton, Spencer Pitman, and the rest of the FLUX Collective

We’re a ragtag band of systems thinkers who have been dedicating our early mornings to finding new lenses to help you make sense of the complex world we live in. This newsletter is a collection of patterns we’ve noticed in recent weeks.

“I like big systems and I cannot lie.”

— Sir Mix a System

🛑🚪 The sticky door

If you take a wrong turn in an urban grid of two-way streets, recovery is cheap and easy. You circle the block and try again. But if you accidentally merge onto the freeway, your options quickly narrow — no U-turns, no off-ramps for miles, and a long recovery before you’re back on track.

That’s the difference between shallow and steep recovery gradients. In both cases, the move is technically reversible. But one costs you 30 easy seconds while the other might cost you 15 stressful minutes.

A valuable model for decision-making is one-way vs two-way doors. However, it’s worth adding some nuance. Many decisions are technically reversible, but the path back is long, uncertain, and full of organizational or reputational cost.

This is where considering the recovery gradient comes in handy. We ask not just “Can we reverse this?” but “How hard or expensive will it be to reverse this — and will we actually do it?”

Take a product launch. You could walk back a rushed feature, but if it damages trust, confuses customers, or exhausts your team, that recovery is uphill. Or a reorg could be theoretically reversible, but if it triggers attrition or saps morale, the reversal cost may be too high to attempt.

Subjective perception plays a huge role here. Some might see a slight slope where others see a cliff. This difference in judgment — not just about the decision, but about how it feels to recover from it — explains why teams can debate endlessly without clarity.

The first step is understanding the recovery gradient. But even better is if we go beyond classifying the decision. We can design the terrain. When the gradient is too steep, can you flatten the slope? Delay commitment? Add side paths? For instance:

Instead of a full pivot, start a special projects team.

Instead of reorging the entire company, make small edits to the most critical teams.

Instead of changing your core pricing, test a new model in a limited segment.

If exploring new markets, use market research and MVPs to test the waters.

None of these ideas are new. Instead, it’s interesting to think of them through the lens of increasing reversibility by making gradients shallower.

But beware that some decisions come with inherently steep gradients. After a layoff, you can rehire but you’ll never get the same team back. Shutting down a product can destroy customer trust and momentum. Announcing a major strategy shift can permanently change your perception in the market.

Reversibility is helpful. But recoverability can matter more. In a dynamic system, decisions should be shaped not just by possible outcomes, but by how hard/expensive it is to backtrack when the terrain surprises you.

🛣️🚩 Signposts

Clues that point to where our changing world might lead us.

🚏🏪 Japanese stores are using robots remote-controlled by workers in the Philippines

Over 300 convenience stores in Tokyo have started using AI-powered robots to restock their shelves. But if the bot drops an item, a remote worker in the Philippines—armed with a VR headset—takes control and moves the robots’ limbs to pick it up. Given Japan’s aging, shrinking, and (therefore) expensive workforce, outsourcing work to Filipinos (who earn about $300 a month) can cut operating costs substantially. The robotics company is collecting data from the workers’ interventions and selling it to a startup that’s trying to build AI models for robots, with the hopes of ultimately replacing the human teleoperators with fully autonomous robots.

🚏🧾 AI-generated receipts are driving “expense fraud”

Employees at many companies can submit receipts for professional expenses to an online portal and get them reimbursed, but the makers of these expense management tools are warning that some workers are submitting AI-generated receipts in an attempt to defraud their bosses. AppZen said that 14% of “fraudulent documents” submitted for reimbursement were fake AI receipts, compared with none last year; Ramp said it had flagged over $1 million in “fraudulent invoices” in the span of 90 days. These AI-generated images are apparently quite convincing, including wrinkled paper, signatures, and items that match real restaurant menus.

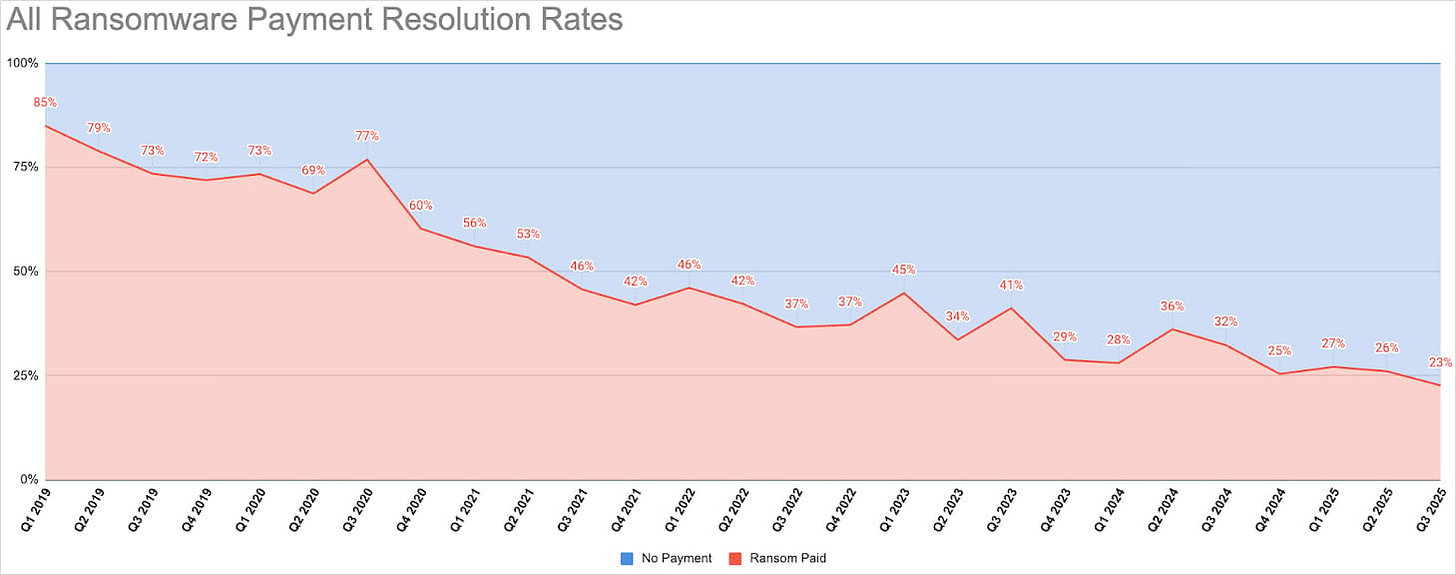

🚏🥷 Ransomware profits are dropping as victims refuse to pay

A new report found that just 23% of companies who fall victim to ransomware attacks are paying the attackers, down nearly fourfold from 85% at the start of 2019. During this same period, though, the median ransom payment has grown from just a few thousand dollars to well over $100,000, indicating that attackers have shifted to targeting a few large “whale” companies rather than a broad “mid-market.” Still, the industry’s profits are decreasing as victims are wisening up and trust between the various actors (attackers, software vendors, affiliates, infrastructure providers, etc.) continues to fracture.

🚏🧑💼 Consulting companies’ stocks are way down due to AI and economic uncertainty

The S&P 500 index is up over 50% in the last two years, but the stocks of several major management consulting companies (including Accenture, Capgemini, and Tata Consulting Services) are down by about 30% in the same time. These firms’ bread-and-butter is offering IT and other services for far less money than it’d cost clients to do it themselves, but AI can do these same tasks for even less money, thus pushing down the prices that consultants can charge—or even removing the need for them entirely. Plus, inflation and “economic uncertainty” is leading clients to tighten their budgets, and the US government (a huge client) has cancelled “multiple billion-dollar contracts” in an attempt to save cash.

📖⏳ Worth your time

Some especially insightful pieces we’ve read, watched, and listened to recently.

The Useful Idiots of AI Doomsaying (The Atlantic) — Argues that AI doomers like Yudkowsky project human-like desires and motivations onto what are essentially bullshit-generating machines incapable of distinguishing truth from falsehood. The real threat isn’t hypothetical superintelligent AI but rather the acceleration of existing Moloch-like dynamics, where tech oligarchs and runaway competitive systems already pursue resource maximization without regard for human wellbeing.

The Hidden Linguistic Messages in Brand Names (PBS Otherwords) — Examines how certain linguistic sounds and patterns have consistent interpretations across languages, from the famous bouba–kiki test to the associations people have with b/d/g sounds (“potent and luxurious”), nasals (tasty food), back vowels (large and heavy objects), and more. Then explores how brands use these patterns when naming products to position them in the market.

Long Degeneracy: Hypergambling Eats the World (Oldcoin Bad, Newcoin Good) — Argues that wealth inequality and hyperinflation in asset prices (most notably in homes) has led young generations to believe that the “linear” path (get a steady job and save up) will no longer let them achieve their goals in in any reasonable amount of time. As a result, people are resorting to asymmetric bets so they can get a shot at wealth; think crypto, sports betting, options or buy-now-pay-later. But this is all effectively gambling, and gambling just loses you money in the long run, meaning that money will flow even more to the winners—thus perpetuating the cycle.

First Shape Found That Can’t Pass Through Itself (Quanta Magazine) — Describes a classic geometry question (can a copy of a 3D shape pass through the same shape?) first explored by England’s Prince Rupert in the 1600s. Most objects have this “Rupert property,” so many mathematicians believed they all did—until two friends recently proved that a certain 152-faced polyhedron (which they dubbed the “Noperthedron”) can’t be passed through itself.

🔮📬 Postcard from the future

A ‘what if’ piece of speculative fiction about a possible future that could result from the systemic forces changing our world.

// 20XX. A suburban living room, before dinner.

“How was your day, kids? Did you have a good time at school?”

“Ugh... it was awful. We are doing this ‘recent history’ section and we had to watch a bunch of videos that television news crews recorded as filler that they would show as intros or filler during broadcasts. A bunch of it got left in some building after the ‘teevee’ station shut down, and they found it a few years ago.”

“Yeah, the teacher kept going on and on about how this ‘found footage’ was culturally relevant and highlighted ‘shifting cultural norms’. Mostly, it was just creepy!”

“Yeah, everyone was standing around in public doing stuff that we know is just bad for you! “

“I can’t believe how many people were just staring at their phones!”

© 2025 The FLUX Collective. All rights reserved. Questions? Contact flux-collective@googlegroups.com.

Regarding the sticky door model, I'm super curious if you guys find certain types of decisions in tech or everyday life just inherently have a steeper recovery gradiant than others, kinda like a default setting, you know? This breakdown of one-way doors versus those with hidden steep recovery costs is seriously insightful, makes you really reflect on planning ahead.