🌀🗞 The FLUX Review, Ep. 131

February 1st, 2024

Episode 131 — February 1st, 2024 — Available at read.fluxcollective.org/p/131

Contributors to this issue: Dimitri Glazkov, Jon Lebensold, Erika Rice Scherpelz, Robinson Eaton, Ade Oshineye, Justin Quimby, Neel Mehta, Boris Smus

Additional insights from: Ben Mathes, Alex Komoroske, Spencer Pitman, Julka Almquist, Scott Schaffter, Lisie Lillianfeld, Samuel Arbesman, Dart Lindsley, MK, Melanie Kahl

We’re a ragtag band of systems thinkers who have been dedicating our early mornings to finding new lenses to help you make sense of the complex world we live in. This newsletter is a collection of patterns we’ve noticed in recent weeks.

“The common trait of people who supposedly have vision is that they spend a lot of time reading and gathering information, and then they synthesize it until they come up with an idea.”

— Fred Smith, Overnight Success

💻🛸 The Babbage machine phenomenon

Computational devices have a long history, but credit for the first computer often goes to Charles Babbage for his Difference Engine and Analytical Engine. However, Babbage’s ideas, while viable, were never actually built. It would be another 100 years before vacuum tubes kick off practical machines for generalized computation.

Protein folding, electric cars, and the many ideas of Leonardo da Vinci show that ideas often show up as concepts or novelty items well before they achieve scale. Sometimes, it takes time for ideas to diffuse. Sometimes, society needs to get used to them. Maybe ideas need technology that hasn’t been invented yet or can’t yet be scaled. Maybe they just need some tweaks before they’re ready for prime time. Sometimes, people were just interested in investing elsewhere at the time.

However, even when these early concepts didn’t yield practical inventions at the time, they are often seen in retrospect as the precursors to later technological development.

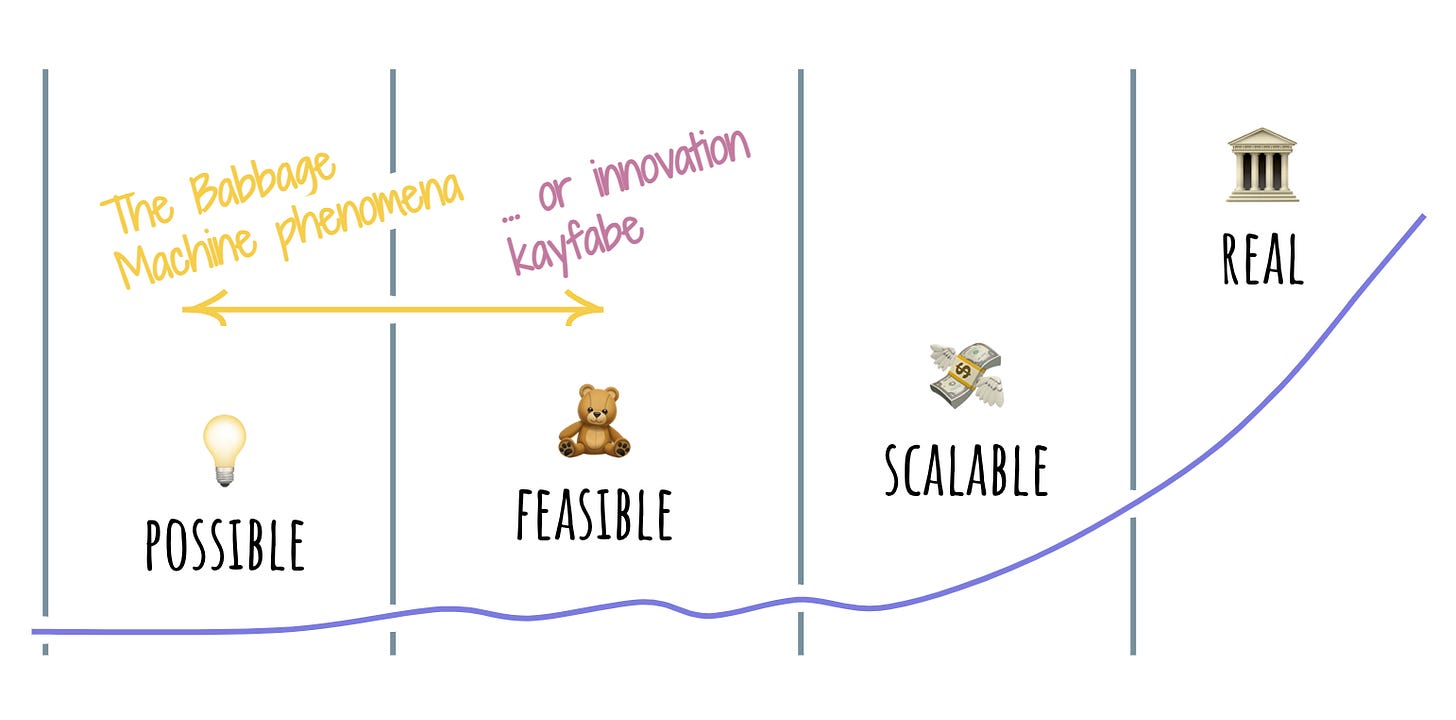

We might call such early glimpses of possible societal-scale innovation breakthroughs “Babbage machine phenomena.” What differentiates a Babbage machine phenomenon from innovation kayfabe (seemingly innovative work that is ultimately just for show)? To some degree, only time can tell. However, by looking at the stages an innovation goes through, we can start to understand some of the differences.

We can imagine a pipeline of innovation from “possible” to “feasible” to “scalable” to “real”:

At the “possible” stage, an innovator takes something previously unimagined (or, perhaps, only abstractly imagined) and shows that it’s possible to work out enough details to build it. Solar sails are an example of a possible technology.

The “feasible” stage shows that the possible can be done in real life with individual care and attention. Many Kickstarters start with a piece of feasible technology: they have a real working demo, but they haven’t yet necessarily made it through the process of validating that they can manufacture at scale.

In the “scalable” stage, innovators focus on figuring out how to do their work without having to do everything by hand. Those Kickstarters figuring out the manufacturing process are at the scalability stage, as are many startups when they roll out their products to be generally available (often greasing the wheels with incentives).

The difference between scalable and “real” is often more a matter of degree than of kind: does society recognize this innovation as generally useful? Can it sustain itself without the incentives propping it up? In a post-ZIRP world, we’re seeing how many startups that thought they were real were still scaling, leading to failures as cheap money and demands for profitability showed they didn’t have a sustainable business model.

Babbage machine phenomena and innovation kayfabe happen in the early stages: possibility and feasibility. This is partially because the cost goes up further along the pipeline. However, it’s also somewhat definitional; by the time something is scaling or beyond, it’s no longer a concept, real or fake.

But back to the original question: how do we spot the difference between Babbage machine phenomena and innovation kayfabe? First, we can start peeling back the layers. Are there detailed plans or just shiny concept videos? The more people are willing to describe how something could work, the more likely we’re looking at a true Babbage machine phenomenon. The more shallow the presentation, the more likely it’s innovation kayfabe. (That said, concept videos can be valuable for inspiration; they only become innovation kayfabe when they are presented as something that’s coming). Is there a real prototype or demo? Are the creators willing to let the public play with it? The more people can poke and prod at the innovation, the more likely it is to be a precursor. In resource-rich environments — such as tech companies during the ZIRP era — the difference might be less about the technology itself and more about the willingness to continue investing (or to set the idea free). Is a good-faith effort made at scaling, or is the effort dropped after a publication, a good press release, or a successful promotion?

Of course, not all innovative paths lead somewhere. We are not driving steam automobiles or (usually) watching 3D televisions at home. However, when it comes to Babbage machine phenomena, the more important question is whether or not a particular idea expands our collective adjacent possible. Ideas, even if ultimately infeasible, help us add to the net wisdom of humanity by better understanding what we can and cannot do. That alone makes them worthwhile.

🛣️🚩 Signposts

Clues that point to where our changing world might lead us.

🚏🎙️ The creators of an “AI” comedy show revealed it was actually human-written

Earlier this month, a podcast called Dudesy released an hour-long comedy special that it claimed was an AI-generated impression of American comedian George Carlin; they said the AI had been trained on “decades” of Carlin’s stand-up material. But when Carlin’s estate sued the podcast for making “unauthorized copies” of Carlin’s “copyrighted routines,” the podcasters said that the comedy special hadn’t used AI at all — instead, one of the co-hosts had written the whole thing. Commentators said this could eliminate some copyright claims, but even an entirely human-written special would still be on the hook for “unauthorized use of Carlin’s name and likeness for promotional purposes.”

🚏⚛️ Investment in quantum computing dropped by nearly 50% last year

Quantum computing attracted $2.2 billion in worldwide venture funding in 2022, but that figure fell to just $1.2 billion in 2023, in part because the AI boom drew away investor interest and in part because investors got more cautious in general. Interestingly, the decline wasn’t evenly distributed: quantum funding fell 80% in the US but just 17% in APAC, and it actually grew 3% in EMEA.

🚏🧑✈️ A study found that coding copilots increased code churn and reduced code reuse

A recent whitepaper that looked at 153 million lines of changed code concluded that the rise of AI-powered coding assistants, such as GitHub’s Copilot, has put “downward pressure on code quality.” In particular, the paper estimates that the amount of code churn (the percentage of lines “reverted or updated” within two weeks of being written) will be twice as high in 2024 as it was in 2021. It also finds that AI-assisted programmers tend to use more copy-pasted and AI-generated code while reusing and refactoring existing code less, which hurts maintainability in the long run.

🚏☀️ FEMA will pay states to install solar panels and heat pumps after disasters

The US’s Federal Emergency Management Agency helps communities recover from natural disasters by funding things like debris removal and the rebuilding of public infrastructure. The agency recently announced that it’ll also start paying for recovering communities to set up solar panels (since microgrids can make communities more resilient to blackouts) and install heat pumps and energy-efficient appliances (to reduce the chance of power outages to begin with).

📖⏳ Worth your time

Some especially insightful pieces we’ve read, watched, and listened to recently.

How Technology Interacts With Status Signaling (Culture: An Owner’s Manual) — Examines how new technologies can both “serve as an antidote to status marking” (for instance, new technologies eventually diffuse and become omnipresent, thus no longer being exclusive) and create new ways for people to signal status (for instance, new technologies often come with “alibis,” or non-status reasons for owning the item, thus making the owner seem less status-focused while still signaling their status).

Contextualizing Elagabalus (The Historian’s Craft) — Uses the case of an oft-maligned Roman emperor to argues that, in the ancient world, history was largely a form of literature, so historians often skewed the truth to fit the themes, motifs, archetypes, and morals that ancient readers expected. Historians also purposely bad-mouthed past emperors to make the current regime look better, often using regional or ethnic stereotypes.

Why Bad Strategy Is a ‘Social Contagion’ (McKinsey) — A business professor critiques executives who conflate goals with strategies; in truth, strategy is all about making a plan to achieve those goals, focusing on the strengths of the company, and mitigating the parts of the plan that make it difficult.

How Language Nerds Solve Crimes (PBS Otherwords) — Examines how forensic linguists use syntax, word choice, sociolinguistics, and statistics to help identify serial killers, thwart ransomers, and even figure out the true authors of books.

🔍📆 Lens of the week

Introducing new ways to see the world and new tools to add to your mental arsenal.

This week’s lens: Tamagotchi quality.

Back in the 1990s, Tamagotchis were all the rage. If you were of the right age, you may have worried about the well-being of your digital pet and heard the chirps coming from other people’s pockets reminding them to do the same. This was the era of the Nintendo 64, the Sony PlayStation, and many other classic consoles. In an environment of such rich digital entertainment, why was a toy with a low-resolution LCD screen so popular?

Tamagotchis were at the sweet spot of doing something truly satisfying really well. They perfectly matched technology with entertainment — at the right time in the curve of technological progress. They were innovative, but they weren’t cutting-edge. We can remember our small digital friends and call this Tamagotchi quality: the idea of solving a problem really well, even if that means doing something that might seem like it’s not pushing us to the edge of our capabilities.

The opposite of Tamagotchi quality is when a technology is pushed beyond its capabilities to create something that presumably solves a problem but is unreliable. Dollar store toys that break under contact with a real child are one example. However, things can fail to meet the Tamagotchi quality bar without being cheap, as technological flops like 3D home televisions or the Juicero gadget. These devices trade performance for a perception of innovation and fundamentally disappoint their users after a few moments.

Tamagotchi quality is related to lateral thinking with seasoned technology, which finds new ways to use existing technology. It is also related to the MAYA and LAYA principles, using the most or least advanced yet acceptable technology to build products that meet your users where they are. Ultimately, this lens highlights the intersection of these principles: that it’s better to do a useful thing solidly than an exciting thing badly.

As we think about current AI technologies, we can apply the Tamagotchi quality lens. Are we trying to use AI to do something that is sustainably satisfying (even if it feels somewhat boring), or are we chasing after innovative ideas where we can only deliver disappointment when they fail to live up to our expectations?

© 2024 The FLUX Collective. All rights reserved. Questions? Contact flux-collective@googlegroups.com.