🌀🗞 The FLUX Review, Ep. 118

September 21st, 2023

Episode 118 — September 21st, 2023 — Available at read.fluxcollective.org/p/118

Contributors to this issue: Neel Mehta, Boris Smus, Dimitri Glazkov, Erika Rice Scherpelz, MK

Additional insights from: Ade Oshineye, Gordon Brander, Stefano Mazzocchi, Ben Mathes, Justin Quimby, Alex Komoroske, Robinson Eaton, Spencer Pitman, Julka Almquist, Scott Schaffter, Lisie Lillianfeld, Samuel Arbesman, Dart Lindsley, Jon Lebensold

We’re a ragtag band of systems thinkers who have been dedicating our early mornings to finding new lenses to help you make sense of the complex world we live in. This newsletter is a collection of patterns we’ve noticed in recent weeks.

“I think that it is a relatively good approximation to truth… that mathematical ideas originate in empirics. But, once they are conceived, the subject begins to live a peculiar life of its own and is… governed by almost entirely aesthetical motivations. In other words, at a great distance from its empirical source, or after much "abstract" inbreeding, a mathematical subject is in danger of degeneration. Whenever this stage is reached the only remedy seems to me to be the rejuvenating return to the source: the reinjection of more or less directly empirical ideas.”

— John von Neumann

💦 🔬 Sweat the details

We spend a lot of time in the world of abstract ideas, but how do we put these ideas into practice? A key practice is grounding our abstractions in reality – we need to sweat the details. After all, no abstraction is perfect. As the saying goes, all models are wrong but some are useful. A useful model is one whose predictions hold when compared against reality.

This is especially true when it comes to organizational change efforts, whether executing a new strategy or motivating a team. The act of leadership requires big picture vision and sweating the details. Sweating the details means thinking about everything that stands between a change effort and its successful implementation: How do people actually execute the change? What questions will they have? What actions will they need to take? We need to be brutally honest with ourselves about where reality is going to cause issues for our ideas.

Sweating the details isn’t about mapping out every minute aspect. It does not mean micromanaging when we should be delegating. To the contrary, involving others increases creativity, credibility, and buy-in.

So how do we sweat the details without falling into micromanaging or analysis paralysis? Let’s use an example of a product team that has had a great high-level insight: “our key problem is retention!” Now we have a great high level goal: improve user retention. If we’re not sweating the details, we might just say, “Go forth team! Increase retention!”

Sweating the details requires realizing it’s not as obvious as declaring “I would simply improve retention”. We can start by listening for questions and doubts. Do we know what “retention” means? Is it repeated usage of any part of our product or just key parts of it? How often do users need to be using our product? For how long? There are important differences between a product used once a month to access pay stubs and one used multiple times a day to communicate with teammates. Treating retention as just a numbers game is how we end up with, say, a glut of superfluous social features in places they aren't needed.

Once we start hearing the questions, we need to ensure that our team is able to come up with answers. We need a robust, validated, and continuously updated theory of change. What factors drive our goals? How do we know that? How will we know we have met our goals? As we describe our change effort at this level of detail, we’ll start to see the cracks. We’ll see the places where our story becomes unrealistic or risky, allowing us to revise it until the whole thing makes sense both to those who set the high-level objectives and those who know the details of execution.

Note what isn’t specified here: this theory of change doesn't dictate how to implement these actions. For example, if we decide a key factor impacting retention is task completion speed, that doesn't prescribe whether we improve algorithms, upgrade our hardware, or overhaul the UI interaction model to make it easier for the user to achieve their job-to-be-done. That said, implementation details like these still need to be robustly connected to the goal. If we know what controllable input metrics level up to your overall goal, then they provide a helpful interface between the goal and the implementation.

This same process works in reverse. When we have a solution looking for a problem, we can work upward from the solution to gauge its expected impact. We might have a deeply held belief that adding a particular feature will enhance our product and improve usage. How will it do so? Is this feature truly critical, or are others more likely to move the needle? What will users do differently once they have this feature? Is that user change important to our goals?

When we’ve developed a robust theory of change, when we’ve sweated the details to ensure our story bridges between abstract models and those concrete details in a way that even hardened skeptics can accept, we carve a clearer path forward. This not only improves our chances of success, but also, crucially, our rate of learning.

🛣️🚩 Signposts

Clues that point to where our changing world might lead us.

🚏🦾 A new factory will mass-produce humanoid robots for use in manufacturing

A robotics company is completing a factory in Oregon that’ll build humanoid robots called Digits, which are designed to work alongside humans in warehouses and factories; the factory will be able to build up to 10,000 Digits a year. The bots were designed with a “human form factor” so they can “lift, sort, and maneuver while staying balanced” and operate in environments originally built for humans, such as those that involve stairs or require crouching. The company will be its own first customer, using the robots to move materials around its own factory, but it’ll start selling the robots next year.

🚏🌧️ Hyperlocal weather forecasters are becoming influencers in India

A community of Indian weather enthusiasts are gaining popularity for their hyperlocal weather forecasts, which they share on social media channels like YouTube and WhatsApp; they often outperform government weather agencies that lack the resources for localized predictions. These “influencers” use publicly available data, personal weather stations, and their own observations to offer timely advice to locals: for instance, one PhD student shares weather patterns with local farmers in a WhatsApp group and also helps tourist-friendly towns know when to shut down attractions, such as when heavy rain is predicted. (However, scientists warn that these influencers may not always have the training or expertise to give accurate predictions.)

🚏🎓 US college enrollment dropped by 4 million in the last decade

According to a recent report, the number of people enrolled in American colleges dropped by 4 million from 2012 to 2022. COVID-19 and the rise of online courses account for some of the shift, but a factor that surprised researchers was the question of ROI: 45% of surveyed high school grads who didn’t go to college agreed with the statement, “getting a college degree is not worth the investment, because I cannot afford to go into debt when I am not guaranteed a future career path.” In a similar study, 78% of American students, and 66% of students worldwide, said they’d prefer it if “my university offered the choice of more online learning if it meant paying lower tuition fees.”

🚏🛰️ A drug-manufacturing spacecraft isn’t being allowed to return to Earth

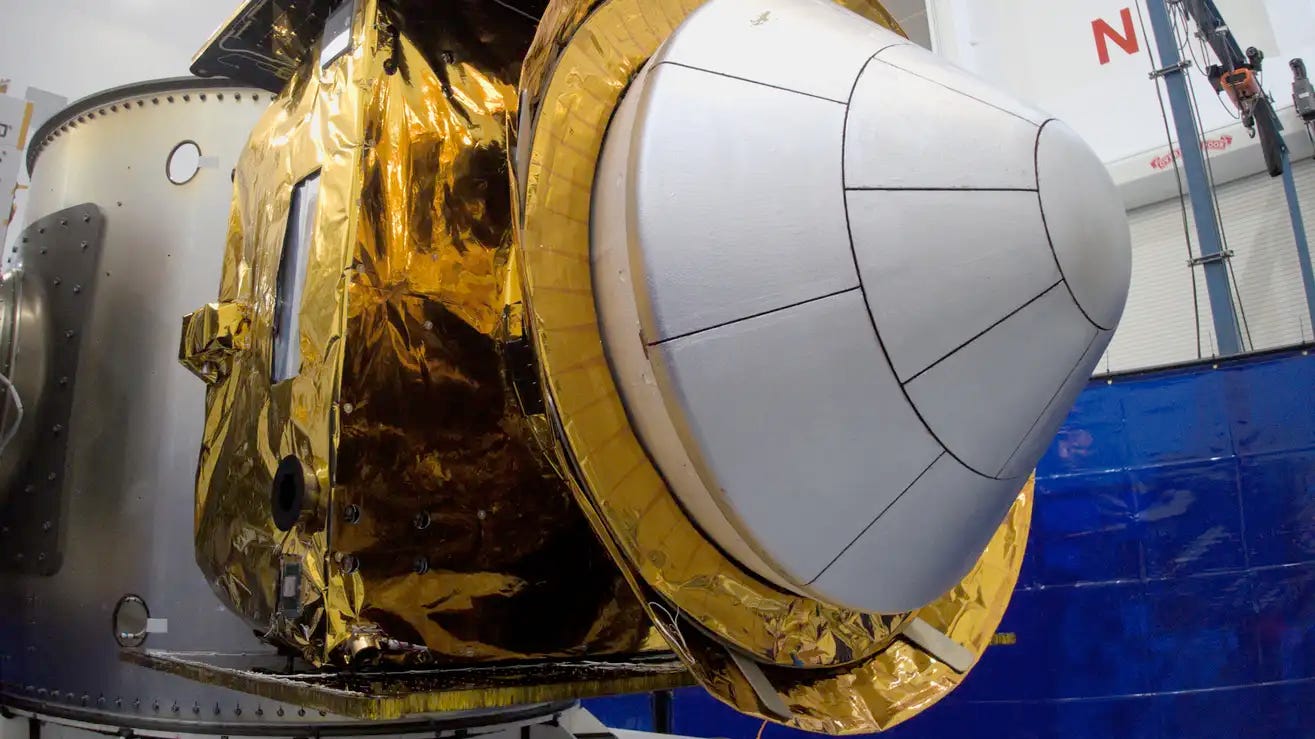

Earlier this year, one startup launched a space capsule that can manufacture crystals of ritonavir (a drug used to treat HIV) while in orbit; it’s been found that protein crystals grow better in space because earthly gravity can induce defects. The company wanted to have its protein factory land in Utah, but the US Air Force denied its request due to concerns about “safety, risk, and impact analysis.” The company says the capsule was designed to last a year in orbit, but they reportedly don’t yet have a backup plan for how to bring the capsule back down to Earth.

📖⏳ Worth your time

Some especially insightful pieces we’ve read, watched, and listened to recently.

The Tyranny of the Marginal User (Ivan Vendrov) — Argues that consumer software tends to get worse over time because companies have to start catering to the lowest common denominator in search of further user growth. This undermines the complexity and quality of software, leading to minimal user agency, infinitely scrolling feeds, and low-value content as businesses prioritize attracting long-tail users with short attention spans, for whom TikTok is just a swipe away.

Toward Parsimony in Bias Research (Oeberst & Imhoff via Steve Stewart-Williams) — Discusses a new paper that argues that the hundreds cognitive biases that psychologists have found all “boil down to one of a handful of fundamental beliefs” (such as “my group is a reasonable reference” and “I make correct assessments of the world”), plus confirmation bias.

What Do We Do With the Twitter-Shaped Hole in the Internet? (Chelsea Troy) — Argues that Twitter’s core job-to-be-done is recommendations (that is, propagating information through the network), and to recreate that in a new social media product, you need to move away from the concept of “one person, one User object” and toward a data model built on feeds and topics. You also need a more nuanced and context-sensitive way of assigning reputability scores to people than a binary “verified” flag.

How ‘Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny’ De-Aged Harrison Ford (Wired) — A compelling look at the use of de-aging technology in the film industry; the tech brings audiences back in time, much like this installment of the Indiana Jones franchise. Yet “de-aging saves no one… what persists are digital ghosts: haunting and eternally youthful.”

🔍📆 Lens of the week

Introducing new ways to see the world and new tools to add to your mental arsenal.

This week’s lens: the adjacent possible.

This lens, introduced by the biologist Stuart Kauffman and popularized by the author Steven Johnson, is one of the most profound, foundational lenses. We at FLUX were rather surprised to find we hadn’t explicitly talked about it yet. It’s time to correct this omission.

When setting out to innovate, we may be tempted by the idea that anything is possible. The sky’s the limit if we dream big enough and think boldly enough. When our ambition is eventually hampered by reality (as it always is), we recognize that there’s actually a more limited set of moves we can make from where we stand. This set of moves is our adjacent possible — the possibilities for the future that are directly adjacent to what exists today.

No matter how much we struggle to invent a car, if we haven’t invented the gasoline engine (or equivalent company means of locomotion) we are unlikely to succeed. If we aspire to innovate in microbiology, but haven’t yet discovered something like a microscope, our aspirations will remain a wild fantasy.

Every new invention is the adjacent possible of some previous invention. Despite us often experiencing technological shifts as breakthroughs, each and every one of them is an incremental change built on what was possible before. Inventions don’t occur in a vacuum. They accrete around other inventions.

Steven Johnson has a lovely metaphor in his book Where Good Ideas Come From (which we reviewed in Ep. 30): “the history of cultural progress is, almost without exception, a story of one door leading to another door, exploring the palace one room at a time.” The future is more or less pre-determined by the adjacent possible of our present.

Such limits may seem like a curse, but they are also a gift. Along this journey through the palace of cultural progress, there are countless doors that are waiting to be opened. Some doors we try fail to open. As our adjacent possible shifts, we will discover that some of those doors now open to reveal new wonders.

© 2023 The FLUX Collective. All rights reserved. Questions? Contact flux-collective@googlegroups.com.