🌀🗞 The FLUX Review, Ep. 111

August 3rd, 2023

Episode 111 — August 3rd, 2023 — Available at read.fluxcollective.org/p/111

Contributors to this issue: Ben Mathes, Erika Rice Scherpelz, Neel Mehta, Boris Smus, Ade Oshineye, Dimitri Glazkov

Additional insights from: Gordon Brander, Stefano Mazzocchi, Justin Quimby, Alex Komoroske, Robinson Eaton, Spencer Pitman, Julka Almquist, Scott Schaffter, Lisie Lillianfeld, Samuel Arbesman, Dart Lindsley, Jon Lebensold

We’re a ragtag band of systems thinkers who have been dedicating our early mornings to finding new lenses to help you make sense of the complex world we live in. This newsletter is a collection of patterns we’ve noticed in recent weeks.

“It’s remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.”

— Charlie Munger

⏳🧠 To build long-term you have to remember long-term

Success creates calluses. In a physical system or a process, this will look like patches and seemingly non-removable inefficiencies. But what about in human systems? In human systems, the lessons learned from the past are built up in our collective memory.

Collective memory is key for the growth and longevity of an organization. This memory is where organizational learning is stored. It enables groups to build and improve over time. Organizations with a robust collective memory can learn from the past. This allows them to act better in the present and plan for the future. We need collective memory to progress sustainably in the long run. Organizations with little collective memory — whether from rapid turnover or incentives to forget — struggle to compound and build over longer periods of time.

Slime molds are capable of living in both single-cell and multi-cell configurations at different points in their life cycle. They implicitly store the patterns of the collective in their single-cell form. Individual memory plays a similar role in forming the collective memory of an organization. Each individual, akin to a cell within a slime mold, carries their own unique memory. This individual memory, an amalgamation of their experiences, successes, and failures, feeds into the whole.

However, the translation of individual memory into collective memory is not automatic. Each individual holds both the inner story of their personal memory and the outer story of the organization. When there is tension between the two, organizational memory suffers. Sometimes our organizational culture reduces that tension. Other times, it can increase it, often in surprising ways.

When organizational incentives too strongly favor novelty and constant reinvention, it can make it harder for an organization to remember. Too much searching for shiny new things can be antithetical to learning. Why is this? The push to continually innovate can inadvertently suppress the incorporation of long-standing individual memory into collective memory. There's an inherent tension between the drive for innovation, which often involves the creation of something new and untested, and learning from past experiences. For organizations, just as for individuals, memory consolidation takes time but is critical to learning. When there’s a constant drive toward newness, individuals within an organization may fail to take the time to consolidate their previous experiences.

A way to balance the tension between shiny newness and learning is to measure success over an aligned memory window. If a leader (or individual) kicks off a project that will take around 4–6 years, their evaluation should have a lookback window of similar length. If the memory window is shorter, like the time since the most recent performance review, then the organization will fail to see the larger story arc of successes and failures and how they reflect larger organizational patterns.

Organizations that wish to learn and grow must cultivate a culture that balances innovation with incorporating the long memories of individuals into the collective memory. This could involve rewarding knowledge sharing, creating platforms for historical knowledge exchange, ensuring that new strategies are informed by past experiences, and a reward system that extends over an appropriate length of time. Done well, gardening an organization’s collective memory will help it to learn more quickly. In the long run, that’s the pathway to sustainable innovation.

🛣️🚩 Signposts

Clues that point to where our changing world might lead us.

🚏🎨 A new AI art generator can be trained in 4 minutes

Nvidia researchers unveiled an AI art generator called Perfusion, which can be trained in 4 minutes and weighs in at just 100 KB; it’s said to be able to outperform popular AI art tools like Stable Diffusion 1.5 and Midjourney in specific scenarios. Perfusion’s central new technique is “key-locking,” which connects a user-specified concept to a broader category during training (such as linking “cat” to a broader “feline” category) to avoid overfitting while allowing for greater variability in the generated art.

🚏🚁 China is limiting drone exports over “national security concerns”

Starting on September 1st, the Chinese government will impose export controls on drones and related equipment, such as imaging and radar gear, lasers, and anti-drone systems, due to “national security concerns.” This decision, which could impact the ongoing war in Ukraine where drones are increasingly being used, also comes amidst tit-for-tat export restrictions (also based on “national security concerns”) between the US and China over high-tech products.

🚏🏘️ The world’s largest 3D-printed housing development is under construction

The world’s largest neighborhood of 3D-printed houses is under construction near Austin, Texas, with its first completed house recently unveiled. This neighborhood will include 100 homes made using a concrete-based material called Lavacrete, which is “piped” into place with 46-foot-wide robotic printers. The architects said that this new method could promise faster and more affordable homebuilding, which would help address the US’s housing crisis, but critics warned about the environmental impact of using carbon-intensive concrete and the need for new building codes for 3D-printed structures.

🚏☢️ The first all-new US nuclear reactor in decades is now live

The first U.S. nuclear reactor to be built from scratch in decades, Unit 3 at Plant Vogtle in Georgia, has commenced commercial operation, making nuclear power now account for about 25% of Georgia Power’s energy generation. The project suffered from significant cost overruns (it cost $35 billion instead of the projected $14 billion) and delays (it was supposed to start generating power in 2016), but regardless, it’s now live and pumping out enough electricity to power 500,000 homes and businesses.

📖⏳ Worth your time

Some especially insightful pieces we’ve read, watched, and listened to recently.

LLAMA2 Isn’t “Open Source” — And Why It Doesn’t Matter (Alessio Fanelli) — Argues that the concept of “open source” needs to evolve in the context of LLMs. Models that we call “open source” may have open- or closed-source training datasets, downloadable or non-downloadable weights, or varying amounts of restrictions on commercial use. Indeed, even in traditional software, the definition of “open source” has gotten fuzzy, blurring with “source available” and conflicting somewhat with “free software.”

Everything Is Cyclical (Collab Fund) — Argues that, whether in nature, human societies, or business, what goes up must also go down. Successful businesses sow the seeds for their own downfall: large and successful firms draw in competitors, invite complacency instead of ambition, and suffer from bureaucratic bloat. The only solution to this inevitable decline is to manage your expectations and relationships to keep your peak as long as possible.

Being and Time, Part 1 (Simon Critchley) — The first in a relatively accessible 8-part series dedicated to Martin Heidegger’s magnum opus “Being and Time,” a notoriously difficult but also insightful and influential philosophical masterwork from the mid-20th century.

How World War I Fueled the Russian Revolution (History) — Explores how WWI exposed and exacerbated Russia’s internal problems, including economic and industrial weakness, outdated leadership, and social unrest. Combined with the consequences of the war, including resource shortages and heavy casualties (due in part to Czar Nicholas II’s poor military strategies), this led to widespread discontent at the monarchy, culminating in the 1917 Russian Revolution.

🔍📆 Lens of the week

Introducing new ways to see the world and new tools to add to your mental arsenal.

This week’s lens: hysteresis.

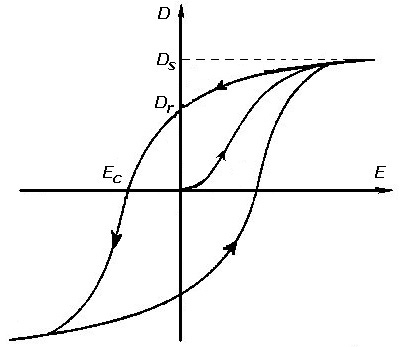

Think of the last time you ate too much because you didn’t realize you were already full. There is a delay between our stomach being full and it telling our brain that we are full. The delay causes us to react more slowly and continue eating beyond what we might want. Although not the most profound of examples, this is an example of hysteresis.

Hysteresis is a property of a system that causes an expected impact to lag behind the intervention because of delays in the feedback loops of the system. Hysteresis happens everywhere, from physics to human organizations.

We are much better off when we recognize hysteresis early. Otherwise we may be tempted to oversteer: “Ugh, my intervention still isn’t working! Pedal to the metal!” We overcorrect, but we don’t realize we did until it’s too late. It’s a great puzzle that, in a world brimming with hysteresis, humans are so poor at dealing with it. There’s something about delays that confuses us and leads us to zig-zag awkwardly and into the pendulum-like extremes of the bullwhip effect.

Armed with the knowledge of hysteresis, we have the opportunity to do better. Next time a system (be that an organization, another person, or your own body) doesn’t seem to react to an intervention, pay attention: where are the delays? What are the feedback loops that show them?

It is only when we experience the discomfort of hysteresis that we are able to detect these delays. Some of them might be as precise and mathematical as magnetic fields. Some might stem from organizational resistance to change. Some might come from poor communication – like in the example of our brain and our stomach. Whatever the cause, hysteresis is a prime opportunity to study systems, understand their properties, and develop effective interventions to shift them into new states.

© 2023 The FLUX Collective. All rights reserved. Questions? Contact flux-collective@googlegroups.com.

Neat write up! I appreciate the part about hysteresis, but in human/organizational systems the only relevant feedback loop is memory, right? In a physical system, changes are worked into the environment - history is instantiated in a magnetic field, or potential energy is held in the temperature or form some substance - but in a business, or for a person with bad eating habits... changes in the world, in the open system these things are inside of will add noise or entirely omit the kind of physical histories a closed system exhibits. Single point failure supply chains, the loss of skilled personnel in a business, or the signals of a full stomach can all be ignored, obscured by complications and abstraction away from whatever relevant, direct feedback might be occurring, until there is a critical failure - crash! Closed business, diabetic condition - permanent system change.