Episode 31 — December 9th, 2021 — Available at read.fluxcollective.org/p/31

Contributors to this issue: Boris Smus, Dimitri Glazkov, Neel Mehta, Justin Quimby, Ben Mathes, Erika Rice Scherpelz, Alex Komoroske

Additional insights from: Ade Oshineye, Gordon Brander, a.r. Routh, Stefano Mazzocchi, Robinson Eaton

We’re a ragtag band of systems thinkers who have been dedicating our early mornings to finding new lenses to help you make sense of the complex world we live in. This newsletter is a collection of patterns we’ve noticed in recent weeks.

“And revolution is coming: not the one that we have been waiting for, but another one, each time another one.”

— Octavio Paz

🌐🛐 The web of belief

The believers heralded Web 1.0 as a revolution. The 1996 Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace proudly proclaimed:

“Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.”

It was a vocal rejection of the status quo, buoyed by the foundational notion that the Internet would change everything.

The fervor and intensity among some groups bordered on the edge of religious belief. Belief — belief in the potential of the new world, belief in the ability to supersede the power structures of the old world — belief fueled the creation of new technologies: web browsers, WebVan, Kosmo.com, Pets.com, Tribe.net, Yahoo, and startups too numerous to count. The dot-com bubble eventually burst. But in doing so, it left behind the physical and digital infrastructure foundations for Web 2.0.

In our current moment, “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” (A phrase often apocryphally attributed to Mark Twain.) The raw, sheer belief that web3 will change the world rhymes with the Web 1.0 discussions of 25 years ago. These beliefs are not necessarily wrong. The web has indeed changed the world, even if it wasn’t as quickly or as thoroughly as the first wave of believers hoped. However, then and perhaps again now, the path from here to there will have unexpected twists and turns, some of which will look like failure at the time.

During the dawn of Web 1.0 in the 1990s, people furiously debated which was the best networking protocol: 100VG-AnyLAN or Ethernet. Back then, we mostly didn’t discuss the ways online purchasing at scale could change commerce. For Web 2.0, we debated whether to exchange our data as XML or JSON objects. We rarely debated the impact of user-generated content on elections.

In 25 years, will we look back at the current excitement around blockchains, memecoins, cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and DAOs (Distributed Autonomous Organizations) in the same way? Almost certainly. When the current web3 tide recedes, what will remain? And what can be built from it? It’s likely that the future’s most important changes are just tiny twinkles today — and it’s okay to admit that we don’t know what they are.

🛣️🚩 Signposts

Clues that point to where our changing world might lead us.

🚏🏭 Scientists think they’ve found a green way to make ammonia, which could slash carbon emissions

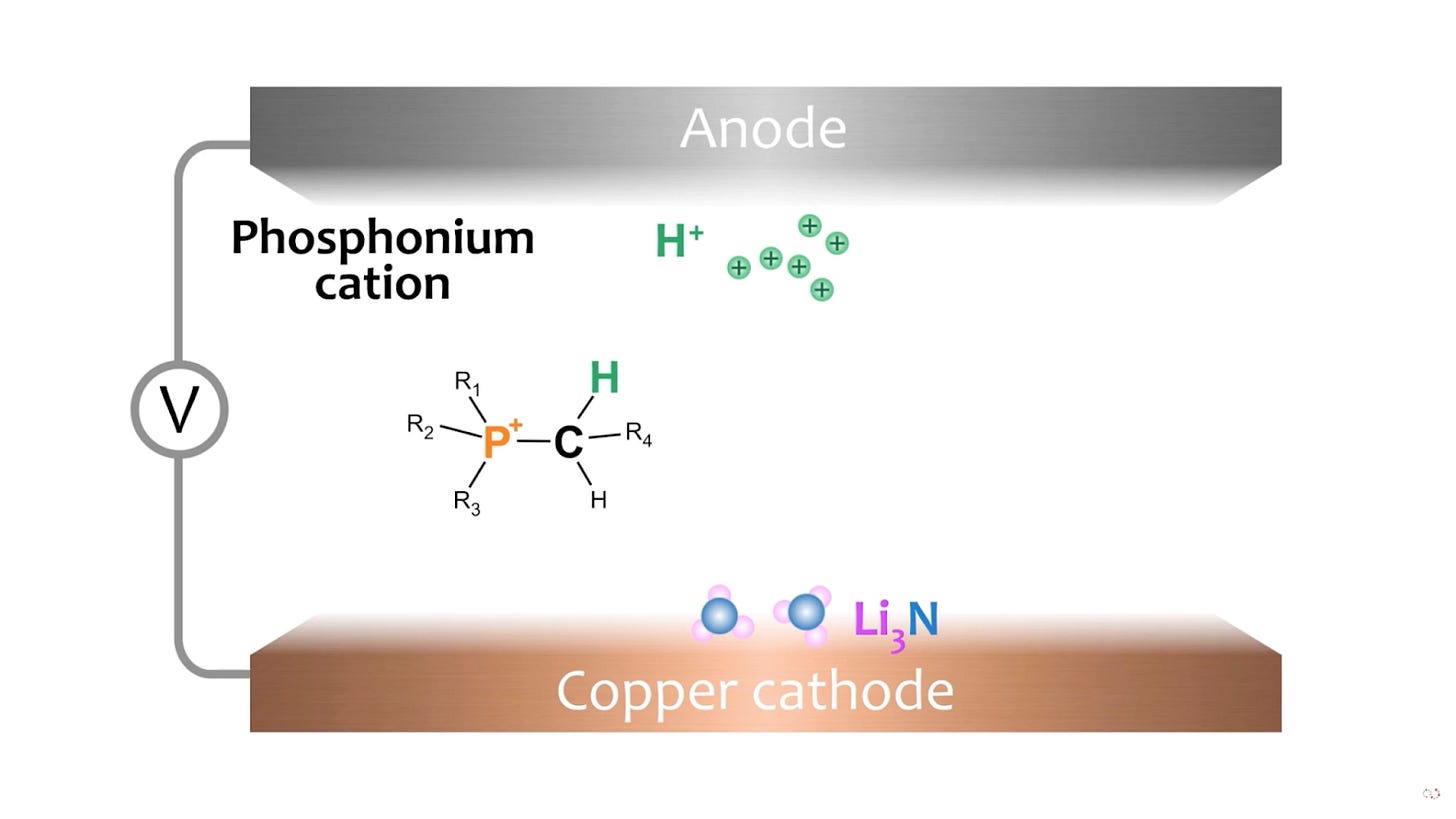

Modern agriculture and manufacturing relies heavily on ammonia, but our primary way to synthesize it — the Haber-Bosch process — relies heavily on natural gas, accounting for 1.8% of global carbon dioxide emissions. But scientists say they’ve made a breakthrough that’ll let them produce ammonia using nothing but electricity, water, atmospheric nitrogen gas, and a reusable electrolysis setup of salts and metals. The new tech is said to be “as clean as the energy used to power it,” highly efficient at room temperature, and able to shrink down to the size of “a thick iPad.” If it works, researchers say it could eliminate all the carbon emissions of Haber-Bosch and would be a key part of a net-zero-emissions future.

🚏🦍 Bored Ape NFTs have their own cartoon show, paired with a new financial vehicle

A new animated comedy series called The Red Ape Family features characters from the buzzy Bored Ape and Lazy Lion collections. While the bizarre YouTube series isn’t particularly popular, each new episode is accompanied by the sale of 333 NFTs. The show’s creators say that 25% of future streaming revenue will be used to buy “blue-chip” NFTs, and holders of the show’s tokens will be entitled to a fraction of these amassed NFTs — thus indirectly giving token holders financial upside if the show takes off.

🚏🌧 The Chinese government manufactured rainfall to clear the air before a big rally

The weather report showed an overcast, polluted sky in Beijing for the day the Chinese Communist Party was slated to celebrate its 100-year anniversary with a massive rally. Researchers found that, the night before the rally, the government launched rockets filled with silver iodide, a chemical known to induce rainfall. This “blueskying” technique was successful: it triggered rainfall over Beijing, improving the air quality and ensuring clear skies for the following day’s celebration.

🚏🗣 A new AI tool will let you create human-like voices given just 30 minutes of speech data

Nvidia has unveiled a new toolkit that will let customers fabricate human-like voices that can “speak” almost any text provided to them. The technology uses semi-supervised learning: if you feed in 30 minutes of a voice actor’s recordings, it’ll be able to generate a full-fledged human voice. Several companies have already started using similar technology: KFC, for instance, created a Southern-accented Colonel Sanders voice to power its Alexa app.

🚏🚢 Amazon is chartering its own private ships and planes to get around supply-chain crunches

These days, buying space on public container ships leads to massive delays as ships idle outside jammed ports. So, Amazon has joined other retailers like Walmart, Home Depot, and IKEA in chartering its own private container ships, which let the company direct goods to relatively less-busy ports. Amazon has also leased at least ten long-haul airplanes to move high-value goods from China to the US more quickly, and it’s even building its own containers in China to get around the container shortage in eastern Asia.

🚏🔖 Thieves are using AirTags to track cars they want to steal

Car thieves in Canada have devised a clever new tactic: they look for expensive cars in public places, attach Apple’s AirTags to them, wait for the cars to move to less-visible places, and then track down and steal the cars at their leisure. Analysts say that AirTags are better tools in this case than rivals like Tile, since AirTags’ larger network of devices make them more accurate trackers. (AirTags do have anti-stalking measures that aim to counteract tricks like these.)

🚏🚁 Scammers are trying to phish people by “airdropping” cryptocurrencies on them

Cryptocurrency addresses are public, and anyone can send money to anyone else without prior approval. The practice of sending coins to people out of the blue, known as “airdropping,” is often used in DeFi projects but has become a new weapon in scammers’ arsenal. The method: send someone some obscure coins named after a particular website, implying that the coins can be sold for cash on that site. But that website is a phishing site, and if the victim connects their crypto wallet to it, the scammers can drain their account.

📖⏳ Worth your time

Some especially insightful pieces we’ve read, watched, and listened to recently.

Is Web3 Bullshit — And Is That Even the Right Question? (Max Read) — Seeks to reframe the polarized “will crypto succeed?” debate by introducing some new mental models, including a 2x2 matrix that tries to tease apart the often-conflated ‘crypto skeptic vs. crypto enthusiast’ axis and the ‘bear vs. bull’ axis.

Lessons from “American Prometheus” (Tim Latimer) — A Twitter thread that extracts insights from the biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the leader of the Manhattan Project. Touches on the “go slow to go fast” school of thought around scientific progress, why bureaucratic streamlining can speed up innovation, and how these lessons can help us in the fight against climate change.

Waiting for the Revolution (The Guardian) — Written in late 2000, this dispatch from the twilight of the dot-com boom tells the story of true believers, rising skepticism, technical advances and limitations, and signs that the “fad” might not go away even after the crash. It makes for a striking parallel with today’s crypto, web3, and metaverse boom.

The Wrong Abstraction (Sandi Metz) — Observes that abstractions have an intrinsic cost and wrong abstractions have a very high cost. In programming, it’s sometimes better to avoid abstractions, duplicate instead, and try a late-binding strategy.

The Bay Area Crime Wave (Darrell Owens) — A housing affordability analyst argues that much of the media fury around department-store burglaries is misplaced: while theft is indeed bad, it’s more productive to focus on how we can break the crime-and-poverty cycle and mitigate the social factors that make people turn to crime in the first place.

Electric Robotaxis May Not Be the Climate Solution We Were Led to Believe (The Verge) — Reviews a new study that projects that, while autonomous electric taxis might pollute less than normal cars, their widespread adoption could actually increase overall emissions, since people would likely ride them solo instead of using more eco-friendly options like carpooling or mass transit.

Simulating a Virtual World... For A Thousand Years (Two Minute Papers) — Gives a visual tour of a paper that uses parameters like climate and geography to simulate the long-term evolution of forest ecosystems. The simulation gives rise to complex behaviors like the gradual replacement of fast-growing shrubs with slow but resilient evergreens — and demonstrates this with beautiful animations.

📚🌲 Book for your shelf

An evergreen book that will help you dip your toes into systems thinking.

This week, we recommend Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World by David Epstein (2019, 352 pages).

Specialists excel in domains with well-defined rules: think trivia, Go, and chess. These so-called “kind” problems have robust statistical regularities that experts can tune into. However, most real world problems are “wicked” and complex. No scenario is quite like the next… or the last.

In Range, Epstein pushes back against the commonly-cited “10,000 hour rule” of specialization. According to him, generalists thrive in wicked domains. Most great people have arrived where they are via circuitous, exploratory routes. They follow their interests and arrive at success somewhat fortuitously. These "dark horses" don't compare themselves to their peers. Instead, they optimize for the match between their interests, their skills, and the job at hand.

Vivid and varied examples abound. Roger Federer took an indirect path to tennis fame, first trying swimming, wrestling, skiing, basketball, badminton, and skateboarding. Vincent van Gogh began as a missionary and only experienced artistic breakthroughs in the last two years of his life. Gunpei Yokoi, a hobbyist, inventor, and tinkerer, helped transform Nintendo from a middling card game company not by competing on shiny gadgets, but by focusing instead on fun gameplay with overlooked, widely-available technology.

Focus and studied practice are not bad — they are often critical! However, this book provides a much needed balance to the idea that they are the most important thing. To find our passion and be our best selves, sometimes we need to flexibly follow where opportunity leads us.

🕵️♀️📆 Lens of the week

Introducing new ways to see the world and new tools to add to your mental arsenal.

This week’s lens: simple rules.

“A stitch in time saves nine.” “Nothing ventured, nothing gained.” Proverbial sayings are so cliché. However, simple rules like these can elegantly capture the gist of complex systemic forces. For example, “a stitch in time saves nine” is a handy way of remembering that problems can grow nonlinearly, so it’s better to solve them when they’re small. Most groups and domains have their own simple rules in the forms of mottos, sayings, and value statements.

Simple rules are not always correct. Complex systems defy being reduced down to simple maxims. What makes simple rules powerful is that they can often be as good as more complicated models while still offering flexibility. Their imprecision is a strength. If the 20-input model with 5 significant figures of output is wrong, then we lose faith in it. If a simple rule doesn’t work, well, we know it’s a simplification. If we ignore a complicated model, we are rebelling. If we ignore a simple rule, we’re showing resilience and adaptability.

Simple rules need to adapt with the system. When exceptions to the rules become the norm, it’s a good sign the adaptation is due. For many years, Facebook had the simple rule of “Move fast and break things.” That was useful when the company was growing rapidly. As the company became a backbone of the world’s social infrastructure, they changed that simple rule to “Move fast with stable infrastructure.”

Once you realize the pros and cons of simple rules, you can use them as a tool for change. Depending on the needs of the situation, you can choose to replace a complicated, precise model with a flexible set of a few simple rules — or, if the system is predictable enough, you can go the other way and replace simple rules with a precise model or process.

You can read more about simple rules in a business context in the book Simple Rules by Donald Sull and Kathleen M. Eisenhardt.

🔮📬 Postcard from the future

A ‘what if’ piece of speculative fiction about a possible future that could result from the systemic forces changing our world.

// With Big Tech companies competing over the same workforce, how will that impact tech recruiting throughout the 2020s?

// 2030. A Fortune Leaders interview.

“So, you’ve built a loyal, productive, and very profitable company in the past decade, during a period of major turmoil in the United States. How did you do it?

“I knew when I started the company that the US was in for a crazy roller-coaster ride, so I wanted resilience. I wanted folks who could be long-term employees, had some connection with their local community, and who big companies wouldn’t even look at because they had no ‘merit signals’.”

“Merit signals? What do you mean?”

“Some folks are lucky and have parents or communities rooting for them. They’re pushed onto the meritocracy treadmill — they get good grades, get into the right colleges, get the right internships, and ‘earn’ an upper class lifestyle. They emit the right ‘merit signals’ for big companies’ recruiting processes. These are ‘Front Row’ students.

“But not everyone has a chance to emit those ‘merit signals’. “I sought out the people outside the elite overproduction gladiator matches — the ‘Back Row’ students. The kids disinterested by school, who didn’t luck into having motivating parents or communities. Every single metric that big companies look at for hiring tends to cut out these Back Row kids. Simple market analysis: a giant cohort of talent that the Front Row system not only didn’t know how to value, but actively didn’t want to.

“My vetting was two-fold: person and place.

For the person:

An online persona demonstrating the ability to work with others; I started with active Fortnite clans and Discord friends

Not too much involvement with crypto pump and dump schemes

At least two credible teachers or community leaders willing to vouch for them

For the place they live:

Recently gutted by hedge funds or other ‘value extractors’, so they’ve got a chip on their shoulder and something to prove

At least one church or a local social institution still going

Not touched by a ‘tech bootcamp scam’

Low risk of climate-change flooding

“It wasn’t easy, as I couldn’t just outsource it to LinkedIn-farming recruiting houses. It paid off when internal American climate change refugees reshaped the US in the second half of the 2020s. My team’s deep roots in their local community combined with their ability to find community online enabled them to thrive. And that’s good for business.”